Quo Vadis—A Unique History Of The Evolution Of The Japanese Patent Invalidation Proceedings

Yuzuki Nagakoshi1

Max Plank Institute for Innovation and Competition and the University of Tokyo

Guest Scholar and PhD student

Munich, Germany

Introduction

For the past 20 years Japan has been continuously revising the patent revocation system, the last revision being enacted in April 2015. This whole process has been a huge endeavor aiming at obtaining the advantages of bifurcated and nonbifurcated systems while minimizing the disadvantages of both systems and maintaining the consistency of the systems. The reform could be understood as a part of the “pro-patent policy” of the Japanese government, aiming at enhanced protection of patent rights. In recent years,2 it evolved into a more goal-oriented “pro-innovation Policy,” which emphasizes more on the innovation generated as a result of adequate IP protection including patents.3

As early as the mid 1990s, the Industrial Property Committee of the Japan Patent Office (“JPO”) pointed out the importance of a pro-patent environment for entrepreneurs, which would allow swift granting of rights and prompt and strong relief in case of infringement in order to increase incentives for companies to innovate.4 The overall direction is still the same now—The Basic Policy Concerning Intellectual Property Policy decided by the Cabinet on June 7th, 2013, (“Basic Policy”) states that Japan should take advantage of their intellectual property assets, and “build up the most advanced intellectual property system in the world, which will attract companies and people from Japan and overseas.”5 Following the Basic Policy, the Intellectual Property Committee of the Industrial Structure Council in the JPO published a report on February 24th, 2014, which mandates the JPO to “make efforts to provide the world’s highest quality patent examination results”6 and to “grant patents that demonstrate legal stability, and which thereby, are not invalidated afterward both inside and outside Japan.”7

In light of the general direction of the national policy, it has been noticed that not only the granting process, but also the revocation process, is a key to “strong” patents.8 Therefore, the revocation system has also been under continuous reform.

Traditionally, Japan had a bifurcated revocation procedure9 similar to the German and Austrian system where patents can only be invalidated in the JPO and not before civil courts as a civil proceeding.10

The reform was triggered with the introduction of the civil court system by the Kilby case11 rendered by the Supreme Court in 2000. Then, the Patent Act reform in 2004 allowed invalidity defense in infringement litigations. With the reform in the case law and the Patent Act, the civil courts can now decide on the validity of the patent when an invalidity defense is raised during infringement litigations. When the courts rule the patents to be invalid, the proprietor would be denied of injunctive relief and damages in the case.

The system differentiates itself from the British style non-bifurcation in the point that the decision on the invalidity does not invalidate the patent with effect to third parties, and invalidity can only be argued in the form of invalidity defense against infringement allegations. The patent decided to be invalid in court is still valid with respect to third parties and theoretically the proprietor can assert the patent against third parties. However, in reality, the court decision will strongly discourage the proprietor from doing so, as the patent will most likely be challenged again and reach the same result as the prior case.

This was the first step for Japan to move toward a hybrid system of bifurcation and non-bifurcation. Since then, Japan continued to modify the system as a response to new issues arising from the previous revisions, to be discussed in detail below.

Patent Revocation System Reform in Other Jurisdictions

Patent revocation system reform is also an international “trend.” The new European Unified Patent system, currently under intense discussion, plans to introduce the non-bifurcated system12 with opposition and invalidity trials. The current idea is strikingly similar to the Japanese system, although an important difference exists in whether the patents could be invalidated in the courts with binding effect to third parties.

Similarly, the United States has been reforming their patent revocation system in order to allow more routes of invalidating patents in the USPTO, acknowledging the defects of their traditional non-bifurcated system combined with high litigation costs. The problem was that questionable patents were left unchallenged and it posed a negative influence on innovation for the following reasons.

First of all, the mere existence of a patent right, even when the validity is questionable, would “scare” others from developing a new technology in closely related fields,13 allowing proprietors to unjustly obstruct competition.14Especially because the invalidation lawsuits are expensive and require actual controversy,15 litigation was not feasible until there was an allegation of infringement and the implementer is threatened with litigation.16 Even if invalidity was argued in court, the courts required “clear and convincing evidence” rather than “preponderance of evidence,” as an issued patent is assumed to be valid.17 This meant that the scales were tipped in favor of the ultimate issuance of a patent.18 In comparison with the historical Japanese or German system, the system in the United States provided stronger protection for weaker patents.

Reflecting on this problem, the U.S. system had gone through a series of reform. In order to invalidate questionable patents in an earlier stage, the cost of litigation in courts was a huge obstacle.19 Therefore, as an affordable alternative, it was suggested that a system should be introduced which allows patents to be challenged in the patent office.

In 1980, ex-parte re-examination20 system was introduced, through which patents could be reexamined on the basis of earlier patents or printed publications.21 Re-examination based on other than the aforementioned two grounds were not permitted.22 In order for the increased involvement of the applicant or requesting party of the re-examination, the inter partes re-examination (IPR) system23 was introduced in 1999, which was reformed into the inter partes review system in 2012.24

The Post Grant Review system (PGR), which allows third parties to file a petition based on all grounds, was also introduced at the same time as the IPR system. The PGR is similar to the opposition system in Japan and Europe in the point that it gives the opportunities for a third party to file a petition to re-examine the patentability within a limited time frame of 9 months based on all grounds. The IPR, on the other hand, is similar to the invalidation trials, as it can be raised any time after the 9-month period has passed or the PGR is terminated,25 however differs significantly in the point that the allowed grounds are limited.

From the examples of Europe and the United States, one could see that the trend in the international “IP leaders” is to move towards a non-bifurcated system with broad invalidation possibilities also in the patent office, with the important exception of the national system of Germany.

Although the aforementioned two prominent examples have attracted much scholarly attention both nationally in their respective country or region and internationally, Japanese legislative history of patent revocation system and legislative history still deserves further international attention. The following paper aims at introducing the legislative history including the underlying considerations of the policy makers and the current status of the Japanese patent invalidation system after the revision in April 2015, in order to evaluate the system as a whole, whether it meets the original purpose of the Japanese “pro-patent” or “pro-innovation” policy, and also to provide a new perspective to the international discussion on the patent revocation system.

Legislative History of the Patent Revocation System In Japan

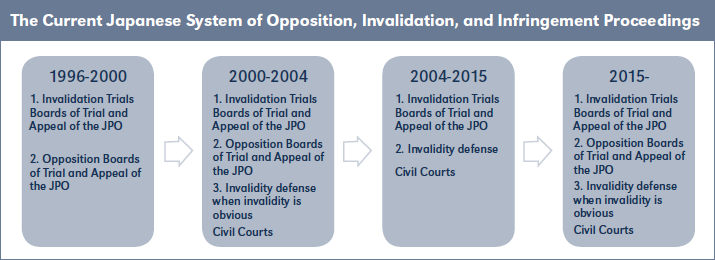

The Japanese patent revocation system was revised several times for the past 20 years, with the latest revision enacted in April 2015. The current Japanese system stands somewhere in the middle of the bifurcated and non-bifurcated systems. The following paragraphs provide an introduction to the reforms of the system and their outcomes, followed by an overview of the current Japanese system as of September 2015.

The Historical System Before 2000

Japan historically had a bifurcated system of patent revocation since 1888, when it introduced the invalidation trial system three years after the introduction of the patent system itself. It later on introduced the opposition system in addition to the invalidation trial system in 1921.26 Since then, up until the year 2000, there were two ways of invalidating patents in Japan, namely pre-grant opposition27 and invalidation trials, both before the Boards of Trial and Appeal of the JPO.28 The system is different from Germany, where only the opposition proceedings are held in the German Patent and Trademark Office29 and the invalidation trials are held in the Federal Patent Court.

During the founding of the patent system in the late 19th century, it has been discussed in the Japanese government whether or not the courts should be involved in invalidation trials, or whether or not the patent office can make the final decision without allowing any opportunity of judicial review.30 At the end, the decision was to adopt a bifurcated system. The rationale was that Japan still did not have enough judges with enough knowledge of the patent law or the patent system, and not enough experts on which the judges could rely on when deciding on validity were available at that time.31 The head of the Patent Bureau at that time, Commissioner Korekiyo Takahashi, strongly asserted that the judges at the time were incapable to decide on the validity, as in order for the invention to be adequately protected, the judges needed to be able to accurately understand the inventions.32 It was therefore not a matter of principle, but rather a matter of practicality why the government at that time adopted bifurcation.33

Before the historical decision in 2000, which will be discussed in detail in the later paragraphs, Japanese courts strictly followed the principle of bifurcation and did not decide on the validity of patents in infringement cases. Furthermore, they chose to automatically suspend the court proceedings until the trial for patent invalidation in the Japan Patent Office reaches a result, following the Supreme Court decision in 190434deciding that the patents are to be regarded as valid until it is invalidated in the trials in the patent office, and in cases where invalidation trials are proceeding before the patent office, the courts must suspend the proceedings until the trials are finished, unlike in Germany where it is the court’s discretion whether or not to suspend the infringement proceedings.

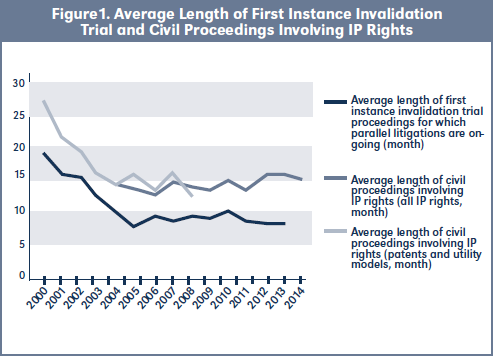

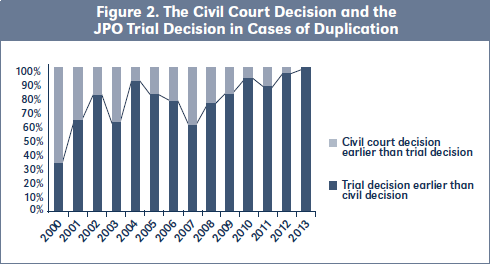

The Japanese way of bifurcation was considered problematic as it extends the period of the court proceedings by automatically staying for the decisions in the trials and then rendering court decisions35 in all the cases. In comparison, the courts look into the cases and suspend them only in cases where there is a high possibility of invalidity in Germany.36 In 2000, which was the last year of strict bifurcation, it took on average eighteen months to reach the first instance decision of invalidation trial proceedings in the JPO (See Figure 1).37 When there were parallel proceedings in the JPO and the civil courts, in over 60 percent of the cases the civil courts rendered a decision earlier than the first instance decision of the JPO (See Figure 2).38

The Transition Period (2000–2004)

The Kilby Case

After a long history of bifurcation, the Supreme Court ruled in the Kilby case (2000) that both injunctions and damages cannot be given based on a patent which is obvious to have reasons for invalidation and is certain to be invalidated if invalidation trials were to be brought up in the patent office. Patent holders seeking injunction and damages based on obviously invalid patents was regarded as abusing their nominally valid patent rights and thus were denied of any relief.

Although invalidity defense were only allowed when the invalidity was obvious to the courts, thus in less obvious cases the courts would not decide on the validity themselves and stay the proceedings, this could be considered as an improvement of protection for implementers or alleged “infringers” of obviously invalid patents, as the proceedings need not be duplicated unless the defendant finds it necessary to invalidate the patent with effect to third parties. Under this Kilby case law there still existed the possibility for the parties to ask for suspension of the trial until the trials in the patent office terminates.

In the Kilby case, The Supreme Court gave 3 reasons for the change of the 1904 case law. Firstly, the original case law posed inequitable disadvantages to the alleged infringer and inequitably benefits the patent holder by assuming the validity of patents even when obvious reasons to be invalid existed. Secondly, to require alleged infringers to invalidate the patent costs too much time and other resources when the “infringer” does not need to invalidate the patent with binding legal effectiveness to third parties. Third, Section 168 (2) of the Patent Act,39 which allows the court to stay the proceedings, should not be applied to cases where there are obvious reasons for a patent to be invalid and it is foreseen with certainty that the patent would be invalid in the trials in the JPO.

The Invalidation System During the Transition Period

From 2000 to 2004, Japanese procedural law allowed three routes to “invalidate” a patent–(i) post-grant opposition; (ii) invalidation trials in the JPO where the decision effects third parties, and (iii) invalidity defense in infringement trials, where the decision binds only the parties involved. Although the court decision is non-binding to third parties, in reality the patent holder would face difficulties if they tried to assert their patent rights previously decided to be invalid in court.

During the same period, the court decisions and the patent office decisions had a high positive correlation.40 The court and the patent office reached the same results for 80 percent of the cases. During the period from 2000 to 2008, the concurrence rate reached 87 percent.41 The patent system allows information exchange between the patent office and the courts when there are parallel proceedings in order to render the decisions quicker,42 which also leads to increased concurrence. In cases in which the patent office and courts reach different results, the appeal would both be brought to the IP High Court, so that the decision would most likely be reconciled there.43

The 2004 Patent Act Revision

Invalidity Defense in Courts

Following the aforementioned Kilby case, the Patent Act was revised on 18 June 2004 with the insertion of Article 104-3. Article 104-3 (1) reads as follows: “Where, in litigation concerning the infringement of a patent right or an exclusive license, the said patent is recognized as one that should be invalidated by a trial for patent invalidation, the rights of the patentee or exclusive licensee may not be exercised against the adverse party.”

Since the text does not include the word “obvious” contrary to the aforementioned Supreme Court decision prior to the legislation, it was disputed among scholars and practitioners whether the revised law broadened the jurisdiction of the courts.44 Some assumed that the opposite was the case: the Patent Office was trying to regain their exclusive authority over deciding the validity of the patents.45 In reality, the courts were deciding under their own discretion in order to expedite the proceedings46 before the law revision and they continued on in this direction.

The Abolition of Post-Grant Opposition Proceedings

At the same time, the post-grant opposition system was abolished and revisions were made to the invalidation trial procedural law.47 The purpose of the original opposition system was to realize public interest by means of public review of patents after grant. However, in actuality, both systems were used as a method of dissolving patent disputes.48 This by itself is not necessarily a problem but more a natural result of the system. The realization of public interest can be achieved through utilizing the opponents’ private interest in invalidating the patent in return for searching grounds for invalidity under a limited time frame.

What really made the co-existence of opposition and invalidation trials problematic were repetitive trials on the same cases.49 The issue of repetitive proceedings was already problematic before the invalidity defense was allowed in 2000. This problem occurred partly due to the fact that the opposition system at that time did not allow opponents to have their opinions heard during the proceedings, and it left the opponent unsatisfied with the results, leading to an invalidation trial launched by the same opponent on the same patent.50 The triplicated invalidation proceedings were considered even more excessive.

The repetitive trials were considered to be problematic in terms of the inefficient use of resources in the patent office and courts, by encouraging challengers to challenge the patents through all possible routes.51 Another consideration was the burden on the patent owners—considering that patents are granted as a reward for invention and disclosure in order to incentivize the inventors, excessive challenge would lead to the decrease of the value of the reward.

Prior to the revision, invalidation actions could only be filed by a person or entity with an interest in the validity of the patent, and opposition actions could be filed by any person or entity.52 In order to allow the general public to invalidate patents without the opposition system, the revised law opened the possibility for persons without legal interest to file invalidation actions, so that the discontinuation would not factually prohibit the invalidation of patents from persons without legal interest.

Post Grant Information Provision System

Another important reform which attracted less attention was the introduction of the Post Grant Information Provision system, which allows any person or entity to provide information concerning the validity of the patent anytime after the grant of the patent. This was aimed at serving as a substitute for the opposition system, which had provided an opportunity to anonymously challenge the patent with relatively low cost.

Providing information will not directly invalidate the patent, but provides support to future challengers during invalidation trials and also the administrative judges who can rely on the information when determining the validity of patents. It does not only benefit the potential challenger, but also the patent owners, as the Post Grant Information Provision System enables the proprietor to check probable reasons for invalidation and amend their claims accordingly.53

The Outcome of the Reforms Until 2004

Swifter Rendering of Decisions

After the Kilby case (2000), the use of abuse of rights defense in court increased dramatically. In all the infringement cases from 2001, the use of abuse of rights as a defense during invalidation proceedings was seen in 26 percent of all cases, whereas in 2002, the rate rose to 49 percent.54 The use of invalidity defense became widely accepted in the Japanese business world.

As a result, the average time needed to issue decisions shortened. In 1998, 130 pending infringement proceedings before the Tokyo District Court were pending for more than 3 years. However, in 2003, the number of pending infringement proceedings which had been pending for more than 3 years decreased to 4 cases. The court had 625 pending cases in 1998, however in 2003 the number declined to 340. The number of cases they decided on in one year doubled from about 200 cases to 430 cases a year.55 As the problem of the former system was that it took too long to reach a decision in infringement litigations, this can be regarded as an expected positive outcome of the reform.

Increased Weaker Patents

Although the intended purpose was met, the Japanese invalidation system faced new problems. The abolition of the opposition system and the introduction of invalidity defense led to increased number of weaker patents.56 This was not only against the direction of the “Pro-patent Policy,” which aimed to rapidly establish stronger and more stable patent rights, but resulted in negative influence in other aspects.

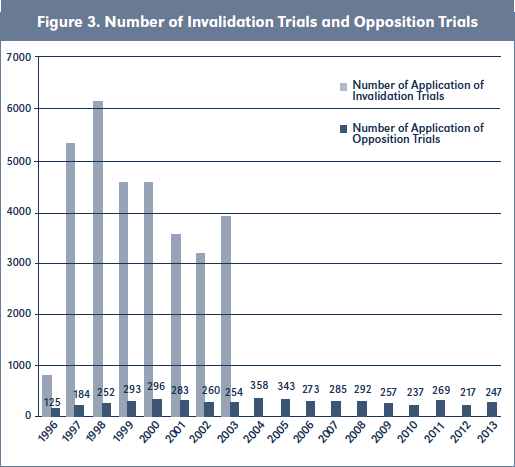

The overall patent invalidation system after the reform discouraged proactive measures of private parties to revoke patents of their competitors by abolishing the opposition system. The intention of the policy makers was to encourage the use of invalidation trials in the JPO instead of the eliminated opposition proceedings in order to maintain the quality of patents. However, the use of invalidation trials increased immediately after the abolition of the opposition system, but decreased after two years, and the number returned to the level of pre-reform.57 Also, after the year 2000 when the invalidity defense was allowed, even the use of opposition trials were declining until it rose in the year 2003, which was the last chance to use the opposition system. (See Figure 3)58 The repetitive trials was a problem of the former system, but having no trial at all was also a problem, as the trials serve as a screening mechanism of erroneously granted patents.

Of all the 3055 opposition proceedings that reached conclusion in the year 2003, 37 percent of them resulted in cancellation of the patents, and another 39 percent were maintained after amendments. A mere 22 percent were maintained in their original form.59 As the use of invalidation trials did not increase, these statistics show that it is likely that questionable patents are left unchallenged under the current system.60

The JPO regards the reason for the reluctance in using the invalidation system to be that potential opponents regard being a party of an invalidation trial too much of a burden, especially because of oral proceedings.61However, the burden of the trial was only the fifth and eighth highest reasons for potential applicants not to start an invalidation action,62 according to the survey conducted by the JPO themselves.63

The reasons for potential opponents to avoid the use of invalidation proceedings was similar to the reasons why potential opponents do not file invalidation in the Intellectual Property Office of the United Kingdom (UKIPO), and it is actually one of the benefits for introducing the non-bifurcated system. It discourages proactive trials, limiting the use of public resources to when actual conflict arises. This would lead to weaker patents, however weaker patents could be a rational choice, as the funding for maintaining the patent system is limited. The only problem is that it does not seem consistent with the Japanese “Pro-patent” policy.

Bifurcation is likely to lead to less proactive opposition or invalidation trials especially when the court proceedings are as attractive as, or more attractive than the trials in the patent office. In Japan, the price difference between the court proceedings and the trials in the patent office is relatively small (the U.K. and the U.S. have discovery in court—Japan does not). Furthermore, Japanese courts do not assume the validity of the patent unlike courts in the United States. These factors contribute to the inclination of potential challengers to wait until an actual conflict arises. Considering the aforementioned evidences and the Japanese invalidation system as a whole, it is rather unclear whether the re-introduction would lead to a return to the original number of oppositions per year.

Different Standards of Validity Between Courts and the JPO

Having the opportunity to attack the patent in court became a better option for the opponent, as the courts maintained higher invalidity rates than the invalidation trials, and at the beginning they had stricter standards when considering validity.64 The courts maintained a high invalidity rate in cases where invalidity defense was brought up by the alleged infringers, due to the courts’ strict interpretation of inventiveness.65 This not only brought reluctance in starting opposition trials in the JPO, but also for launching infringement litigations in court, because of the possibility of being counterattacked using invalidity defense and resulting in the patent being invalidated.66 Since the issue of validity cannot be brought to civil courts unless there is an infringement litigation on that patent, suing an infringer meant that the proprietor would risk factual invalidation in courts under stricter standards than the patent office. However, with the efforts of the courts to harmonize their decision, this problem was gradually resolved. It is pointed out that in recent years, the inventiveness standards are lowered in favor of the patent holder,67 and the invalidity rate declined 10 percent in four years, from exceeding 50 percent in 2007 to about 40 percent.

Overall, as a result, weaker patents were left invalidated, and the proprietors, in fear of invalidity defense based on proof for invalidity that the implementer of the technology had kept to itself68 for this very purpose, became more hesitant to launch infringement litigations.69 The questionable patents which were left invalidated scared current or prospective competitors away from investment in that field, while the patent holders were more reluctant to sue the infringers, which lead to even less challenges of questionable patents in the form of invalidity defense.

The Use of the Post-Grant/Pre-Grant Information Provision System as a Substitute

The post-grant information provision system was expected to substitute the opposition system to some extent, but the number of information provisions per year remained between 57 to 79 cases during the period of 2004 to 2011,70 possibly due to the fact that the provisions would provide the opportunity for patent proprietors to better prepare for possible litigation71 but would not influence the examiner in any way. The use of the pre-grant information provision system which existed long before the continuous revisions started, sharply increased from around 4700 provisions to 6500 in 2011.72 The pre-grant information provision system is considered to be more useful for the potential challengers, because it influences the examiners and could result in the denial of patent grant. However, it still cannot be a complete substitute of the opposition system, as it is only possible during the period between the publication of the patent application and the grant of the patent,73 and due to recent acceleration of the patent grant, increasing number of patents are granted before the publication.

In addition the information concerning the prospective patents are limited compared to already granted patents.74However, the positive effect on the quality of the patent cannot be overlooked. Research shows that the grant rate of patents decrease by 10-15 percent when information is provided before the grant, thus implying that the system provides a screening effect.75

Repetitive Proceedings

Repetitive proceedings were also a major downside of the new system. Even before the introduction of the invalidity defense in courts, repetitive proceedings in the JPO was considered to be a problem, as opponents in the opposition proceedings often launched an invalidation trial when the patent was maintained as a result of the opposition proceedings. This led to prolonged instability of the patent right in question and a heavy burden on the part of the patent holder. In some cases, there were parallel proceedings on the same patent. As the proceedings differed in many aspects the two proceedings could not be merged, and was considered to be an ineffective use of resources of the JPO.76

A similar problem occurred under the new system. Even though alleged infringers in the infringement litigations do not necessarily have to invalidate the patents in the invalidation trial in JPO in order to avoid being held liable for damages for the “infringing” activities or face injunctions based on a patent with reasons to be invalid, almost 74 percent of all cases which happened in the 28 months following the court decision used the abuse of right defense also have parallel trials in the patent office.77 This was almost 30 percent of all patent infringement cases during the period.

There were three possible reasons for this phenomenon. The first was that the obviousness of the invalidity the courts require was rather unclear, thus it was never “safe” to rely on one route. The second was that the results achieved in the court proceedings and trials in the patent office were different—the decisions in the court only binds the parties involved in that proceeding, whereas the decisions of the trials have a binding effect to third parties. If an alleged infringer wishes to achieve broader effects, they still need to invalidate the patents in the patent office.78 The third one is that having two opportunities to argue against the validity of the patents was attractive for the alleged infringers.

In these aforementioned cases where both the invalidity trial and the infringement action where the validity is examined is being held on a particular patent, the validity of the patent is determined independently in the courts and in the JPO, thus resulting in the duplication of the process. While the revision lead to increased speed in rendering decisions, as already mentioned above, it also posed a negative impact towards the efficiency of the use of resources in the court system and the JPO,79 and also resulted in a heavy burden on the part of the proprietor, who needs to defend the patent both in court and in the JPO trial, whereas the alleged infringer only needs to invalidate the patent once in either of the forum.80

The new limited non-bifurcation system also lead to the retrial in cases where the court decides the cases earlier than the JPO.81 Since the effect of the decision of the Patent Office is retrospective, which means that the patent would be regarded as it did not exist from the beginning when the patent is invalidated through the invalidation trial, the problem whether or not to allow retrial arose.

Under the Japanese Civil Proceedings Act Art. 338(1) (viii), when “[t]he judgment of other judicial decision on a civil or criminal case or administrative disposition, based on which the judgment pertaining to the appeal was made, has been modified by a subsequent judicial decision or administrative disposition,” “an appeal may be entered by filing an action for retrial.” When the patent is found invalid in the court and later on found valid in the patent office, the retrial cannot be filed because the “administrative disposition,” in this case, the grant of the patent, is not changed. When the patent is found valid in court and later on decided as invalid at the JPO, the “administrative decision” to grant the patent was changed, and this constitutes a ground for retrial, undermining the stability of the court decision.

In order to address the aforementioned problem, the 2011 Patent Act newly introduced Art.104-4, which prohibits the retrial in cases where the court decision based on the validity of the patents were followed by the invalidation or claim correction in the JPO.

The Reintroduction of Post-Grant Opposition System in 2015

A recent major change in the Japanese patent system was that it reintroduced the post-grant opposition system in April 2015 to provide another alternative for patent invalidation. Similar to the former opposition system, there are no restrictions for the eligibility as an opponent, and the filing must be done within 6 months after the grant of the patent. Patent holders are entitled to make amendments during the process in order to avoid cancellation, and in case of cancellation the proprietor can appeal to judicial courts.

The system is rather similar to the previous postgrant opposition system, but differs in the following three points. Firstly, the examination is conducted based on documentary proceedings in order to lighten the burden of opponents. Second, the opponents may submit written opinions after the patents are amended82 in order to increase the opportunities for the opponent to be involved. Lastly, the amendments for the application of opposition are not allowed after the notification of reasons for refusal is sent to the proprietor.83

The reason given by the JPO for the reintroduction is that the replacement of the opposition system by the invalidation system resulted in discouraging the public from invalidating patents, and lead to less stable patents. Because Japanese patents are increasingly used by Japanese companies as a base patent for foreign patent application, instability has become a major issue.

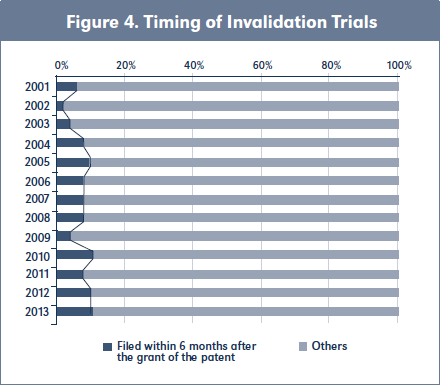

Contrary to the expectation of the JPO after the discontinuation of the opposition system discussed above, there was little increase in the number of invalidation trials. (See Figure 3)84Also, the percentage of invalidation trials filed within 6 months after the grant of the patent did not grow significantly85after the abolition of the opposition system. (See Figure 4)86 This showed that patents were rarely challenged during their lifetime and also during their early stage of life.87 As investments accumulate over the lifetime of the patent, early challenges of questionable patents actually works in favor of the patent holder.88

The Effect of the 2015 Revision

Interestingly, the current law reform seems to be signaling that the JPO is moving toward a different direction from the previous reforms. In the 2004 reform, the post-grant opposition system was abolished and invalidity defense in courts were introduced, resulting in the system where the litigation proceeding is shortened but factually encourages the “infringers” to wait until they get sued. Under the patent invalidation system from 2004 to 2015, low-quality patents were left without being invalidated until the patent owner attempts to assert the patents. This results in less burden for proprietors when they do not intend to litigate against infringers as they “suffer” from less attacks, but more risk when they wish to litigate. On the other hand, the infringers can wait unless they have an immediate threat of being brought to court, but are under constant fear of infringing patents, as they do not know for certain if the existing patents are valid or not.

Now, after the aim of the 2004 law reforms are gradually being met, the 2015 reform is headed toward a system which encourages the competitors to invalidate the patent when it seems to be erroneously granted, which had been the consistent direction of the patent system before the continuous reforms started. The direction in which the Japanese patent revocation system is headed is rather unclear at the moment.

The problem with the new system is yet unclear at the moment, however scholars and practitioners have pointed out the following issues. First of all, under the current system, there exists three routes through which patents could be invalidated, namely post-grant opposition trials, invalidation trials and invalidity defense during infringement litigations, which may result in triplicated proceedings. This may result in stronger patents, but the burden on the part of the patent holder may be too high. Patents are aimed at granting a monopoly to reward the inventor—if the burden is too heavy for the patent holder, the incentive to patent, or to invent, may decrease.

Second, as mentioned above, the use of the opposition system may not go up to the level before the elimination in 2004, as invalidity defense in court has meanwhile became an attractive option for potential opponents. If it is the policy makers’ intention to screen out as much patents as possible, it may be that more incentives needs to be provided to the potential opponent.

The Current Japanese System of Opposition, Invalidation and Infringement Proceedings

As a result of the aforementioned continuous reform, Japanese patents can only be invalidated with effect to third parties in the patent office through invalidation trials or opposition proceedings. In infringement cases under the courts, invalidity defense could be heard,and the court can decide on the validity of the patent. If the courts decide the patents to be invalid, it leads to denial of remedies based on that patent, although the patents still exist and continue to be valid to third parties until it is invalidated in the patent court. The details of the system are seen in the chart below.89

Summary and Recommendations

The patent revocation system plays an important role in the early stabilization of patents, improving the quality of the patents and also in the swift grant of remedies in case of injunction, thus is one of the key elements of the “pro-innovation” policy of Japan. The current patent revocation system in Japan is a combination of bifurcation and non-bifurcation, which was created in order to resolve revocation matters faster and also to improve the quality of granted patents while providing sufficient protection for the patent holders, without changing the core of the bifurcated system.

The time needed to reach decisions both in invalidation trial proceedings in the JPO and the infringement proceedings in the court was drastically shortened as a result of the current patent revocation system. It may well be that it is a result of continuous competition between the JPO and the courts to obtain broader jurisdictions over the validity of patents. This was the positive result of the consecutive amendments on the patent revocation system. However, the goal of improving the quality of patents while adequately protecting the patent proprietors was never achieved.

Reflecting on this shortcoming, one possible solution is that to shift the system to a purely non-bifurcated system with restrictions to avoid duplicity on the revocation procedure. Revising the legislative history shows that it was not a matter of principle that Japan adopted a bifurcated system, but rather a matter of practicality based on the lack of technical experts in the country. Since Japan already has sufficient number of specialists who could advise the judges on the validity of patents, and also has a system where the JPO-trained experts aids the judges in deciding the validity, the very reason for adopting a bifurcated invalidation system, namely the lack of qualified judges and experts available for the civil courts, has already disappeared. It seems possible for 21st century Japan to have a non-bifurcated system where the courts can directly invalidate the patents with effect to third parties. This would possibly lead to less duplicated proceedings in the JPO and the court.

In considering whether the non-bifurcated system creates a “pro-innovation” environment, the stability of the patents, swift and non-repetitiveness of conflict resolution are the factors which should be taken into account. The Japanese “non-bifurcated system” had brought about a tendency to encourage potential challengers to wait until they are accused of infringement, withholding evidence of invalidity because of the tendency of the courts to “invalidate” the patents in comparison with the trials, and also because filing an invalidation would send a message to the opponent that the patent interferes with the challenger’s business activities. Evidence suggests that the strength of the patent has declined, and duplicated proceedings were still a problem, but on the other hand the speed in which the conflict is resolved both at the JPO and courts greatly improved.

To strengthen patents by encouraging early attacks against them, revising the Patent Act 104 (3) and requiring the patents to have “obvious” reasons to be invalid when invalidity defenses are used before the civil courts may be part of the solution. Alternatively, restricting the permissible grounds before the courts (as is the case in the United States) would also have a similar effect. If the complainant of the patent revocation case would be treated more favorably in the JPO than the courts, they may be inclined to proactively use the system in the JPO.

When the aforementioned measures are taken, there may be a difference or inconsistency in the decision of the court proceedings and the JPO proceedings and there will be a probability that relief for infringement is granted based on questionable patents just because it was not invalidated earlier in the JPO. This would encourage the alleged infringers to invalidate the patent earlier in order to enjoy their opportunities to attack the patent in the JPO and then in the courts if necessary, which would result to stronger patents.

The courts can alternatively consider introducing a hybrid system of conditional bifurcation, which involves the court deciding on the validity of the patent when the invalidity or validity is obvious, and for less obvious cases stay the proceedings and rely on the decision of the patent office. This would allow the court to decide early when the cases are obvious and in other cases allow the patent office to decide. This would also probably result in less triplicated or duplicated proceedings, although it may not necessarily result in encouraging proactive invalidation.

Regarding the problem of triplicated proceedings, eliminating one route to revoke a patent may additionally be considered. The opposition system has a distinct aim, namely to remove invalid patents during the early stage of the life of the patent for the public interest, and thus needs to be maintained, especially because if used frequently enough it increases the stability of the patents later on in their life. By contrast, the invalidity trials have a similar aim to the invalidity defense before the civil courts, namely to resolve disputes among the parties. They are also similar in the point that they could be brought up anytime after the grant of the patent. If triple track proceedings are to be too much of a burden, it seems logical that the invalidation trials should be eliminated rather than the opposition system.90

The recent patent invalidation system reforms in major jurisdictions have inspired scholars and practitioners to re-analyze the system as a whole and has ignited a heated debate. As written above, there is not a one-size-fits-all solution. The general direction needs to be in line with the national patent policy of the jurisdiction and the details need to be adjusted in order to function in tandem with surrounding judicial systems. The Japanese “evolution” of the patent invalidation system is still on its way and requires continuous attention and analysis in the future.

Chart 1. Invalid Patent Proceedings |

|||

| Column 1 | Invalidation Trials | Opposition Proceedings | Invalidity Defense |

| Venue | Boards of Trial and Appeal (JPO) | Boards of Trial and Appeal (JPO) | Civil courts in which the infringe- ment litigation is heard (Tokyo or Osaka District Court) |

| Aim | Resolving disputes Correcting the error of the grant of the patent |

Correcting the error of the grant of the patent. Resolving disputes | Resolving disputes |

| Qualification of judges | Technical | Technical | Legal judges, supported by specialists, who are often former trial judges from the patent office or patent attorneys. The assistance of the specialists are compulsory. |

| Appeal | Intellectual Property High Court (Allowed to both parties).

In case of appeals from the trial and the first instance court at the same time, the same panel reviews the validity. |

Intellectual Property High Court (Allowed to the proprietor in case of cancellation of grant) | Intellectual Property High Court (Allowed to both parties). In case of appeals from the trial and the first instance court at the same time, the same panel reviews the validity. |

| Applicant | Person with interest | Anyone | The defendant in an infringement litigation |

| Anonymous Application | Not allowed | Not allowed | Not allowed |

| Participation of challenger | Inter partes | Ex parte but challenger may submit written opinions when the patent is amended as a response to the notification of the grounds of revocation. | Inter partes |

| Period Limitation | Anytime after the opposition period expires | 6 months after the grant of the patent | Anytime (Only during the infringe- ment litigation for the patent) |

| Grounds | All grounds stated in Article 123 of the Patent Act, including Public interest reasons such as novelty, inventive step, inappro- priate, or insufficient description e.t.c;

Entitlement; Grounds subse- quent to the grant of the patent. |

Only public interest reasons such as novelty, inventive step, inappropriate, or insufficient description e.t.c. | Same as the Invalidation Trial |

| Proceedings | Ex officio oral proceedings under the administrative law judges | Ex officio documentary proceedings under a panel of 3 to 5 administrative law judges | Adversary system |

| Estoppel | Parties and Participants cannot launch another trial based on the same facts and reason. | Not applicable | |

| Multiple Proceedings | Proceedings could be merged | In principle all the proceedings are merged | |

| Effect of Decision | Also effective against third parties | Also effective to third parties | Only among the parties taking part in the proceeeding |

| Duplicated Proceedings | The courts may stay the pro- ceedings until the invalidation trial is terminated. In practice the JPO would prioritize the op- position proceedings when there are parallel proceedings. For

the cases on the same patent, the same panel of administra- tive law judges deals with the proceedings in both opposition and invalidation trial. |

The courts may stay the pro- ceedings until the opposition proceeding is terminated.

The invalidation trials may be stayed until the opposition pro- ceedings are terminated. |

The courts may stay the proceedings until the invalidation trial or opposition trial is termi- nated. |

| Average time until Decision

(1st Instance, months) |

7.8 | — | 15.1 |

| Official Fees (JPY) | 49500 per complaint plus 5500 multiplied by the number of claims | 16,500 plus 2400 multiplied by the number of claims | Maximum 1% of the claimed damages

(paid by the losing party) |

| Attorney Fees (JPY, on average) | 377,534 plus 357,128 when successful | 276,630 plus 236,647 when successful (Based on a questionnaire conducted before 2004) |

5-20 million, in difficult cases may go up to 50 million (paid partly by the winning party, but a factual cap of 10-20% of the awarded damages) |

Acknowledgements

This research is a partial result of a research project on comparative patent bifurcation systems conducted at Clare Hall, Cambridge University with the financial support of the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, The University of Tokyo. I would like to thank all the faculty and administrative staff both in RCAST and Clare Hall for being so flexible and cooperative before and throughout the research project.

I would firstly like to thank the faculty and students at Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Law, Cambridge University, including Professor Lionel Bentley, Professor Bill Cornish, Dr. Cathy Liddel, Dr,Yin Harn Lee for all the insights they have provided me throughout the research. Besides the researchers in CIPIL, my sincere thanks also goes to Prof. Sir Robin Jacob, who has also provided me a precious guidance in obtaining a more holistic view of the non-bifurcated system. At the end of this research, Ms. Carrie Bee Hao has aided me in polishing the draft and improve the legibility of the paper from a practicing lawyer’s perspective. I would therefore like to cordially thank Ms. Hao for dedicating her time and great effort in supporting this project. Last but not least, I would like to thank my doctorate thesis advisor, Professor Katsuya Tamai for his continued support in all my academic endeavors.