Fifty Years Of A Changing Landscape For Patents In The United States

James Sobieraj, President, LES International

Brinks Gilson & Lione

Shareholder

Chicago, IL, USA

Licensing professionals have seen dramatic changes in the United States patent system since the creation of the Licensing Executives Society 50 years ago. The paradox of the U.S. patent system during these five decades is that the only constant has been change. At times, these changes have been welcomed by licensing professionals. At other times, they have caused great consternation. This paper will provide an overview of some of the most significant changes concerning U.S. patents that have impacted licensing professionals since the founding of the Licensing Executives Society.

The Skeptical View of Patents During the Early Years of LES

When LES was created in the mid-1960s, patents were an underappreciated asset class in the United States. The federal government and courts seemed more concerned about perceived anti-competitive aspects of patents than their benefits. Federal courts, which have exclusive jurisdiction over patent cases, judged the validity of patents in divergent ways.

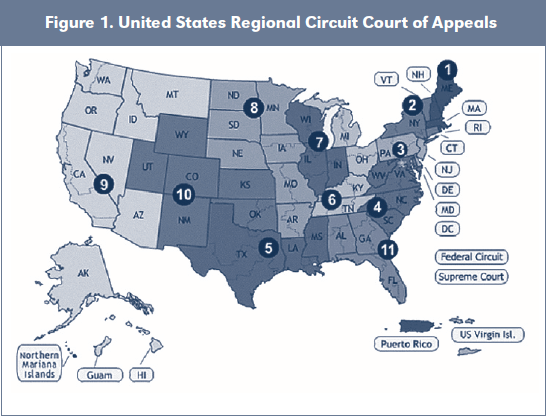

The federal courts in the United States have one or more District Court in each state, and appeals from the District Courts are heard by a regional Circuit Court of Appeals. There are eleven regional circuits as shown in Figure 1. The decisions of a regional Circuit Court of Appeals are binding on the District Courts within its circuit, but are not binding on any other Circuit Court of Appeals or District Court.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the District Courts and Circuit Courts were often unfriendly venues for patents. In some appellate courts, over 60 percent of the patents were held invalid, and the legal standard for invalidity varied among the regional appellate courts. The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals had a reputation as a “graveyard for patents.” The Fifth and Seventh Circuits were considered more likely to uphold the validity of a patent. The lack of a national standard led to anomalous results where the same patent may be held valid in one part of the country and invalid in another party of the country. Consequently, patent owners often engaged in forum shopping to avoid circuits with high invalidity rates. If the case ended up in one of those circuits, the patent owner assumed substantial risk of an adverse result.

This “dark” period for patents reached its nadir sometime in the mid to late 1970s. At that time, thought leaders in business, government and academia came to appreciate that the lack of uniformity and consistency in patent law was undermining the value of patents, providing a disincentive to invest in research & development, and placing the United States at a disadvantage in the face of increasing international competition. Foreign competitors, with lower labor, manufacturing and R&D costs, continued to increase market share by selling products that took free advantage of innovations that originated in the United States. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, momentum was building in favor of stronger U.S. patent rights.

The Creation of the Federal Circuit and Halcyon Days for Patent Owners

The pendulum began to swing toward stronger patents with the creation of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on October 1, 1982. Congress granted the Federal Circuit exclusive jurisdiction over appeals from final decisions of District Courts in cases asserting infringement of a patent, or seeking a declaration that a patent is not infringed or invalid. By doing so, Congress sought to achieve greater uniformity in patent law, and eliminate the type of forum shopping that had resulted from conflicting legal standards in different parts of the county.1 The anticipated result of achieving these objectives was an increase in technological innovation in the United States.

The Federal Circuit accepted its mission with zeal. Within a few years, the Federal Circuit replaced a number of disparate legal standards created in the regional circuits with a nationwide standard that was often beneficial to patent owners. District Court decisions finding patents non-infringed or invalid were being reversed at a rate previously unseen, and in some opinions with strong language portending that invalidating a patent was not to be taken lightly.2

Damages for patent infringement began to take on much greater significance. The Federal Circuit sent an early signal that patents are valuable assets, with its affirmance of a $909 million damages award in favor of Polaroid against Eastman Kodak.3 Damages awards in the tens and hundreds of millions of dollars became more and more common. Prior to the Federal Circuit, District Courts often bifurcated the issue of damages from liability, putting all damages issues on hold until liability was decided. As the patent owner frequently failed to prevail on liability, the party defending a patent infringement case usually could avoid discovery and trial on damages issues. All of that changed in the 1980s. Bifurcation of damages became the exception instead of the rule. Patentees now pursued damages discovery from the outset of a case, concurrently with liability discovery, thereby increasing the scope, burden, cost and risk of defending a patent infringement case.

Patent owners found another arrow in their quiver when the Federal Circuit made it easier to prove willful infringement. The U.S. patent statute allows a patent owner to receive up to three times its actual damages and recovery of its attorney fees in “exceptional cases.”4 A finding of willful infringement is often a basis for finding a case to be “exceptional.”5 Not long after its formation, the Federal Circuit placed an affirmative duty on a potential infringer with actual notice of a patent to obtain competent legal advice from counsel before the initiation of any possible infringing activity.6 Accused infringers defending against a patent without a well-reasoned opinion of counsel faced a substantial risk of paying treble damages and attorney fees. The importance of obtaining an opinion of counsel also imposed a new burden and cost on businesses generally.

The Federal Circuit also adopted a standard for granting injunctions that provided patent owners with more leverage. The traditional test for granting an injunction requires the court to evaluate and weigh four factors: a likelihood of success on the merits, irreparable harm in the absence of an injunction, the balance of hardships to the patentee of not granting an injunction and to the infringer of being enjoined, and an injunction’s effect on the public interest. The Federal Circuit essentially created a presumption that infringement of a valid patent resulted in irreparable harm to the patent owner that was not overweighed by any harm to the infringer or public.7Consequently, patent owners came to expect, and accused infringers came to fear, that an injunction would most likely issue if the patent owner prevailed on the liability issues. The threat of an injunction became a mighty sword in the arsenal of a patent owner.

In Markman,8 the Federal Circuit made clear that construction of the scope of a patent claim is a question of law that it reviews de novo on appeal. The issues of infringement and validity of patent often turn on the meaning of a few key terms in a claim. By ruling that claim construction is an issue of law, the Federal Circuit does not have to give any deference to the trial court’s claim construction. The parties and Federal Circuit could, and did, approach the issue anew on appeal, as if the trial court’s decision did not matter. As a result of these interrelated developments, the Federal Circuit became, as a practical matter, the sole and final arbiter of most patent cases for a number of years.

The Federal Circuit push the pendulum even further significantly expanded the frontiers for patentable in State Street Bank.9 The Court held that there is no per se rule against obtaining a utility patent on a method of doing business. This decision opened the floodgates to new applications for business method patents, which became the currency of many non-practicing entities (a/k/a NPE or more derisively, “patent trolls”).

These intertwined “pro-patent” developments had the net effect of patents more often adjudged valid and infringed, an injunction was likely to issue, large damages awards could be obtained, and if the infringer did not have a sufficient opinion of counsel, the damages may be tripled and the patent owner could recover its attorney fees. It did not take long for businesses, universities and entrepreneurs to appreciate that patents were valuable assets, and to increase their efforts to obtain, license and enforce patents.

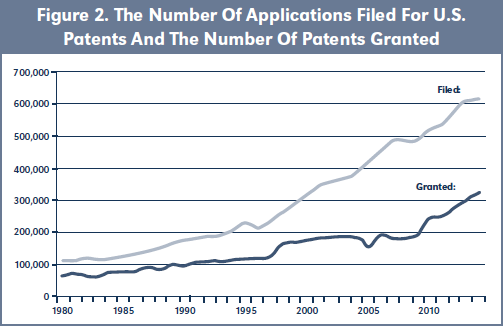

As shown in Figure 2, the number of applications filed for U.S. patents, and the number of patents granted, has increased dramatically since the creation of the Federal Circuit in 1982.

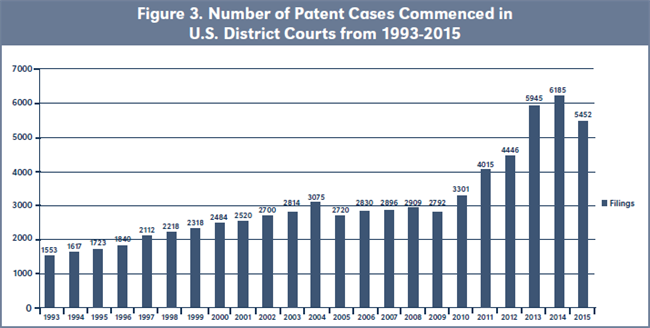

Not surprisingly, the number of patent lawsuits also rose dramatically over the last two decades, as illustrated in Figure 3.

The Pendulum Starts to Slow

The steady stream of pro-patent developments hit a speed bump in the late 1990s, when the Supreme Court intervened and narrowed the circumstances under which a patent can be infringed. Long ago, the Supreme Court established that when there is no literal infringement due to the absence of a claim element in the accused device or process, the patent owner may establish infringement under the doctrine of equivalents.10 The Federal Circuit construed that precedent to mean that “the doctrine applies if, and only if, the differences between the claimed and accused products or processes are insubstantial.”11 The Supreme Court reversed, and narrowed the scope of protection available under the doctrine of equivalents.12

After much criticism about the burden of obtaining an opinion of counsel to avoid willful infringement, the Federal Circuit overruled its earlier decision in Underwater Devices.13 In Seagate,14 the Court held that “proof of willful patent infringement permitting enhanced damages at least requires a showing of objective recklessness.” The Court also held that “to establish willful infringement, a patentee must show by clear and convincing evidence that the infringer acted despite an objectively high likelihood that its actions constituted infringement of a valid patent.” This new standard made it much more difficult for patent owners to prove willful infringement, and recover treble damages and attorney fees.

The growth in the number of patents issues began to attract public criticism as to the quality of patents issued by the USPTO. The United States Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) published a report in 2003, entitled To Promote Innovation: The Proper Balance Of Competition And Patent Law And Policy. The FTC concluded that patents of dubious quality can impede competition and innovation, and offered recommendations for improvement. In 2004, an economics professor at Brandeis University and a professor of investment banking at Harvard jointly authored a book entitled Innovation and Its Discontents: How Our Broken Patent System Is Endangering Innovation and Progress, and What To Do About It. A central theme of the book is that patents have become so strong that they can lead to undesirable economic consequences, that too many questionable patents are being issued, and that the Patent Office needs to shore up the quality of its review of patent applications. In 2011, the FTC published another study, this one entitled, The Evolving IP Marketplace, Aligning Patent Notice And Remedies With Competition. In this report, the FTC argued that vague patent claims in the IT industry helps NPEs obtain higher than justified settlements.

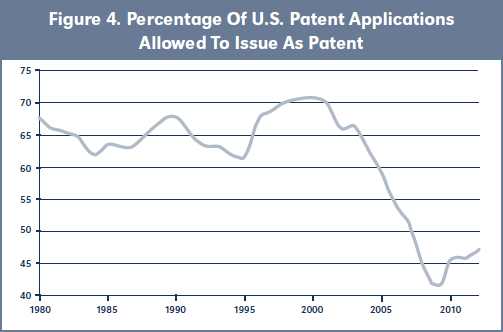

The Patent Office was not tone-deaf. As a result of increasing public scrutiny of the quality of patents, the Patent Office took a number steps to make its application review process more rigorous. As shown in Figure 4, the allowance rate for patent applications declined significantly, from over 70 percent in 2000 to slightly over 40 percent in 2009. More recently, the allowance rate has ticked up to above 50 percent, but still well below its earlier peak.

The Pendulum Reverses: The Contraction of Patent Rights

Over the last ten years, a number of forces have combined to make it increasingly more difficult to obtain, license and enforce U.S. Patents. Two of the most impactful developments are the Supreme Court’s increased attention to patent laws and the creation of inter partes review.

For many years after the creation of the Federal Circuit, the Supreme Court, which has discretion to decide which appellate court decisions to review, consider a relatively small number of patent cases. It seemed that the Supreme Court wanted to allow the Federal Circuit sufficient time to develop its jurisprudence with little intervention from the highest court in the land. As the economic importance of patents, and criticism of that economic power, became more frequent topics of discussion among business leaders, licensing professionals and the media, the Supreme Court became more active in placing its imprimatur on the development of patent law.

In 2006, the Supreme Court issued its decision in eBay v. MercExchange,15 which confirmed that patent cases are no exception for applying the traditional four-factor test for an injunction. The Court rejected what it perceived as the Federal Circuit’s general rule that an injunction should issue if a patent is valid and infringed. Consequently, since the eBay decision, patent owners have found it more difficult to obtain injunctions, and parties charged with infringement perceive injunctions as less of a threat, particularly for patents asserted by NPEs.

In 2007, the Supreme Court made it easier to find a patent invalid for obviousness under 35 U.S.C. §103. InKSR,16 the Court rejected the Federal Circuit’s “rigorous approach” of requiring a teaching, suggestions or motivation (TSM) to combine known elements in order to show that a claimed combination would have been obvious. The Supreme Court noted that TSM is but one of several factors that may be considered in evaluating whether a claimed combination is obvious. Other factors include common sense and whether it would be obvious to try. Following this decision, many more patents were found invalid for obviousness and many more patent applications were unable to overcome rejections based on obviousness.

During 2008, the Supreme Court decided an issue of particular importance to licensing professionals—patent exhaustion. In Quanta,17 the Supreme Court reversed the Federal Circuit, and held that: (1) patent method claims may be exhausted; and (2) the authorized sale of a component of a patented invention may exhaust patent rights when the only “reasonable and intended use” of the component is to practice the patent and the component embodies the “essential, or inventive, feature” of the invention.

The Supreme Court has been particularly active in trying to better define what constitutes patentable subject matter. In Bilski,18 the Court held that claims directed to a method of hedging risk, without recitation of any structural elements, were an unpatentable abstract idea. The Supreme Court rejected the Federal Circuit’s machine or transformation test as the sole test for patent eligible subject matter. Two years later, in Mayo,19 the Supreme Court held that claims directed to administering and determining an effective level of certain drugs in the treatment of autoimmune diseases were unpatentable as a law of nature. The following year, in Myriad,20 the Court held that claims directed to isolated natural DNA are not patent eligible, whereas claims directed to man-made cDNA are patent eligible.

The Supreme Court’s most recent decision on patentable subject matter, Alice,21 has had an immediate, significant impact on patent owners and licensing professionals. In Alice, the Court explained that “the mere recitation of a generic computer cannot transform a patent-ineligible abstract idea into a patent-eligible invention.” Nor is it sufficient for a claim to limit “the use of an abstract idea ‘to a particular technological environment.’” Because the claims at issue did no “more than simply instruct the practitioner to implement the abstract idea of intermediated settlement on a generic computer,” the Court held that they are not eligible as patentable subject matter. AfterAlice, patents directed to business methods and software have been invalidated by the courts at an unprecedented rates, and patent applications on such subject matter have been rejected more frequently in the Patent Office.

In recent years, the Supreme Court has stepped in to address a number of other aspects of patent law. In a decision of great interest to licensing professionals, Kimball,22 the Court reaffirmed its 1964 Brulotte23 decision, where the Court held that a patent holder cannot charge royalties for the use of the invention after a patent has expired. In Nautilus,24 the Supreme Court adopted a “reasonable certainty” test for claim definiteness, holding that the Federal Circuit’s more lenient formulations “can leave courts and the patent bar at sea without a reliable compass.” In Limelight,25 the Court held that liability for induced infringement depends on the existence of direct infringement, and that the Federal Circuit’s analysis of the issue “fundamentally misunderstands what it means to infringe a method patent.” The Supreme Court made it easier for parties that successfully defend claims of patent infringement to recover their attorney fees in Octane Fitness26 and Highmark.27 These decisions gave District Courts more discretion to determine if attorney fees should be awarded, lowered the burden of proof from clear and convincing evidence to a preponderance of evidence, and curtailed the Federal Circuit’s standard of review to an abuse of discretion by the trial court. In Commil,28 the Supreme Court overruled the Federal Circuit and held that a defendant’s belief regarding patent validity is not a defense to an induced infringement claim. In Teva,29 the Supreme Court overturned the Federal Circuit’s long-standing precedent that claim construction is always subject to strict de novo review. The Supreme Court confirmed that the ultimate question of claim construction remains a question of law, but the Federal Circuit must review for “clear error” a district court’s findings with respect to disputed “subsidiary factual findings.”

Another recent development that has had a significant impact on the U.S. patent system and licensing professionals is the rise of inter partes reviews (“IPRs”). After years of deliberations and false starts on patent reform legislation, the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (‘’AIA”) was signed into law on September 16, 2011. While AIA included a number of changes to the patent system, the one that has had the most immediate, significant impact is the IPR proceedings, which became available on September 16, 2012.

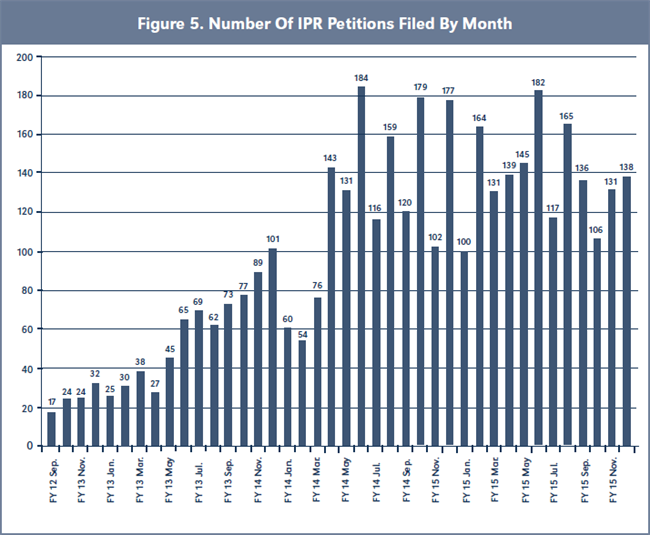

Congress’ objective for IPRs was to provide a faster, less costly alternative to civil litigation to challenge patents. The number of IPR petitions vastly exceeded the expectations of the government, which estimated approximately 500 petitions in each of the first two years that IPRs were available. The actual number filed was approximately twice as much. Figure 5 shows the rapid increase in the number of IPRs filed. The large majority of those petitions were granted, at least in part, and resulted in the invalidation of patent claims.

Looking Ahead

Yogi Berra once said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” Licensing professionals currently are adapting to a number of changes to the U.S. patent system brought about by a flurry of recent Supreme Court decisions and the American Invents Act. The Federal Circuit continues to hone its jurisprudence in light of these developments. Additional patent reform legislation has been proposed, but is unlikely to pass in the presidential election year of 2016. In light of all of the recent changes and uncertainty, it seems relatively safe to predict that changes will continue to occur and that licensing professionals will continue to work in a fascinating, dynamic and economically significant field for many years to come. Enjoy the ride!

- See, e.g., Atari Inc. v. JS & A Group Inc., 747 F.2d 1422 (Fed. Cir. 1984); Christianson v. Colt Indus. Oper. Corp., 822 F.2d 1544 (Fed. Cir. 1987) vacated on jurisdictional grounds and remanded, 486 U.S. 800 (1988).

- Panduit Corp. v. Dennison Mfg. Co. 774 F.2d 1082 (Fed. Cir. 1985), vacated, 475 U.S. 809 (1986).

- Polaroid Corp. v. Eastman Kodak Co., 789 F.2d 1556 (Fed. Cir. 1986).

- 35 U.S.C. § 284 (“the court may increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed”); 35 U.S.C. § 285(“the court in exceptional cases may award reasonable attorney fees to the prevailing party”).

- See, e.g,. Amsted Indus. v. Buckeye Steel Castings Co., 23 F.3d 374 (Fed. Cir. 1994).

- Underwater Devices Inc. v. Morrison-Knudsen Co., 717 F.2d 1380 (Fed. Cir. 1983).

- See, e.g., Richardson v. Suzuki Motor Co., 868 F.2d 1226 (Fed. Cir. 1989).

- Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc., 52 F.3d 967 (Fed. Cir. 1995), aff’d 517 U.S. 370 (1996).

- State Street Bank & Trust Co. v. Signature Financial Group, 149 F.3d 1368, 1369 (Fed. Cir. 1998), cert. denied, 523 U.S. 1093 (1999).

- Graver Tank & Manufacturing Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., 339 U.S. 605, 610 (1950).

- Hilton Davis Chemical Co. v. Warner-Jenkinson Co., 62 F.3d 1512, 1517 (Fed. Cir. 1995), rev’d, 520 U.S. 17 (1997).

- Warner-Jenkinson Co. v. Hilton Davis Chem. Co., 520 U.S. 29 (1997).

- Underwater Devices Inc. v. Morrison-Knudsen Co., 717 F.2d 1380 (Fed. Cir. 1983).

- In re Seagate Tech., LLC, 497 F.3d 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

- eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, LLC, 547 U.S. 388 (2006).

- KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007).

- Quanta Computer Co. v. LG Electronics Inc., 553 U.S. 617 (2008).

- Bilski v. Kappos, 130 S. Ct. 3218 (2010).

- Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Labs, Inc., 132 S. Ct. 1289 (2012).

- Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 132 S. Ct. 1289 (2013).

- Alice Corporation Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014).

- Kimball v. Marvel Enterprises, Inc., 135 S. Ct. 240 (2015).

- Brulotte v. Thys Co., 379 U.S. 29 (1964).

- Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2120 (2014).

- Limelight Networks, Inc. v. Akamai Technologies, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2111 (2014).

- Octane Fitness, LLC v. ICON Health & Fitness, Inc., 134 S.Ct. 1749 (2014).

- Highmark Inc. v. Allcare Health Management System, Inc. 134 S.Ct. 1744 (2014).

- Commil USA, LLC v. Cisco Systems, Inc., 135 S.Ct. 1920 (2015).

- Teva Pharm. USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., 135 S.Ct.. 831 (2015).