Defining Fairness: Promoting Standards Development By Balancing The Interests Of Patent Owners And Implementers

Matteo Sabattini, Ph.D.

Chief Technology Officer

Sisvel Group

Torinese (TO), Italy

1. Introduction

Innovation and technology are fundamental drivers of the world economy. Mobile technologies, in particular, generated a global revenue of around $3.3 trillion in 2014, with more than 11 million jobs worldwide being related to mobile technology, and it is estimated that at least two-thirds of the mobile industry is based on innovation. 37 percent of the $3.3 trillion revenue was generated by mobile devices (components and manufacturing, device retail, etc.), 44 percent by communication services (mobile infrastructure, mobile site operations and mobile operators), the rest was generated by mobile content and applications [BCG].

Innovation is at the core of economic development, and intellectual property is a fundamental tool to protect and foster the phenomenal innovative ecosystem that we have helped create. In recent years, however, we have been witnessing the radicalization of the discussion around intellectual property rights (IPRs), and patents in particular, due to two extreme viewpoints.

On one side, there are companies known as “patent trolls”1 that exploit litigation costs to extort licensing revenues from businesses of any size, including very small ones, on the basis of patents that are often weak or even openly invalid. According to [Saba]:

“But what are patent trolls? And is the monetization of intellectual property per se a troll behavior? Trolls are those entities that bully the market by asserting, or threatening to assert, in court invalid or bogus patent portfolios to industry players that do not have the resources to defend themselves or for which it does not make economic sense to fight back in court. They seek quick settlements by asking relatively (compared to the cost of defending against those patents in court) small sums. By creating risk and exploiting the exorbitant costs of litigation (especially in the U.S.), patent trolls are often able to extort, in aggregate, significant sums. Many companies, especially in the past, settled in the fear of the residual risk.”

On the other end of the spectrum, there is a growing number of stakeholders that equate licensing revenue of any sort with “extortion,” even if said revenues are used and reinvested in research and development (R&D). Academic literature abounds that have tried to quantify the costs associated with patent trolls and non-practicing entities (NPEs) as a whole [Bess], [Chien], often relying on weak (or even bluntly incorrect) assumptions or flawed arguments2 [Quinn].

Some industry players have gone as far as to equaling injunctions with extortion. This is not only ethically wrong, but also shamefully deceiving. Injunctions, in reality, are a fundamental property right, and a matter of justice to prevent unauthorized use of technologies. Without injunctions, patent owners will be left power-less against the theft of their innovations. Unfortunately, most people do not understand what injunctions really are and what purpose they are serving. Those players, rather than favoring a balanced debate, are fueling a populistic view of injunctions as being bad for the whole industry while simply trying to reduce their costs for using somebody else’s technologies. Fortunately a recent decision [ECJ] by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) clarified the requirements for patent owners to obtain injunctive reliefs (refer to the discussion in the following sections).

The recent public debate on patents and costs associated with licensing and litigation is purposely blurring the line between NPEs and trolls. We need to stress that research labs, universities and individual inventors are all NPEs. However, those who are supporting this argument have a clear economic interest to disqualify all NPEs as trolls: they simply want to avoid paying royalties to inventors! In doing so, they apparently want to destroy the good reputation of universities, research institutes, inventors and, ultimately, all innovators. There are legitimate business models—which include all those actors, from universities to for-profit, high-tech companies that rely on technology and IP licensing to fully or partially fund their R&D activities—and extortionists.

It is incorrect and ultimately morally wrong to classify these entities as trolls. By forcing them to forego monetization of their technologies through licensing, we would undercut their ability to further invest in innovation [Saba]. Individual inventors, academics, research universities and R&D labs have contributed and contribute immensely to global technological advance and welfare [Niro].

The innovation and high-tech ecosystem must recognize that using poorly-designed instruments such as overly broad legislation or shortsighted policies that do not distinguish between legitimate, reasonable and appropriate licensing activities on the one hand and the extortion-like activities on the other hand, harms the entire industry [Saba]. We encourage members of the IP community, as well as governments, committees and judiciary branches to seek the advice of multiple stakeholders (technology companies, universities, licensing entities, individual inventors, etc.) and not heed only those who shout loudest or with the deepest pockets.

2. General Considerations

In the following sections, we will highlight some arguments that we support and believe needs to be addressed and considered in a balanced discussion about IP licensing and policy. These arguments are the following:

- The importance of innovation to increase wealth:

As demonstrated in many academic works, thriving economic times have been anticipated and matched by significant industrial and technological progress. The innovation ecosystem as a whole is a fundamental driver of global prosperity. - The importance of global standards and Standard Setting Organizations:

International standards and SSOs have played—and will have to play—a vital role in the definition and dissemination of technologies that are now at the core of society, first and foremost mobile technologies. Let us make sure we do not place unnecessary, artificial burden on the SSOs’ work that could hinder their future relevance. - The innovation loop:

Investments in R&D can create a self-sustaining cycle in which the results of previous innovation can fund new research, generating an innovative loop in which intangible assets acquire a tangible economic value. - The myth of a litigious industry:

Often-cited articles with questionable assumptions have been widely used to fuel the rhetoric of growing litigation, while other solid academic works that have disproved or questioned those assumptions have often (intentionally?) remained unnoticed. - How to cope with unwilling licensees:

There is a need to restore a balance between inventors and technology adopters. What are the remedies left to patent owners, especially individual inventors or small companies, when large corporations refuse even to enter into licensing discussions? - Global implications of local nuisances:

While the problem of patent trolls also exists outside the U.S., litigation costs in North America have unfortunately encouraged extortion-like behavior of a few bad players. However, global policies that will have overreaching effects should not be biased nor one-sided and require thorough economic analysis.

The above topics are of crucial importance and have global implications. Any dialogue about IP that does not take them into consideration will necessarily be biased and guided by self-interest rather than societal welfare.

2.1. The Need to Protect and Foster Innovation

As noted above, innovation benefits from and requires multiple actors, including individual inventors, universities, research centers, start-ups, high-tech manufacturing companies and service providers.

Many of these cited actors fear that a growing anti-patent sentiment and proposed regulations could place unnecessary burden and constraints on their technology transfer and licensing activities, ultimately making IP irrelevant. And that will inevitably lead to lower revenues from IP, less resources to re-invest in R&D and less willingness by researchers to spend time on generating IP, and, ultimately, less innovation [Mason]. When it comes to recent changes of the IEEE patent policy, even a globally-recognized innovator like Irwin Jacobs is concerned [Jacobs].

Some efforts at the policy making level are heading in the right direction: the European Union has been leading and vigorously supporting the innovation ecosystem with its digital agenda. The “Horizon 2020” framework is just one example of the commitment the EU has taken with respect to research and development. Moreover, special-purpose programs have been established to support small and medium enterprises (SMEs). These programs aim at guaranteeing participation of, and contribution by, all stakeholders to the EU’s innovation agenda.

2.2. The Importance of Global Standards and SSOs

Since the advent of the pan-European GSM telephony standard, the EU and its member States have been active proponents of an open platform to spur innovation and enhance participation by all stakeholders, especially in the ICT sector. A vibrant and effective innovation ecosystem based on open standards has emerged also, thanks to the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI). The results and benefits to society of such efforts are there for all to see.

Innovation is required to increase the speed, the reliability of the connection, the battery life, in order to deliver better services at even a lower cost. SSOs such as 3GPP are the collector of new ideas from innovators, deputed to convert those ideas in public documents, software code, technical reports and specifications then used by any company to manufacture interoperable products. Of course, all the activities conducted within SSOs require huge investments by all participants (in terms of R&D spending, but also for active participation to standardization meetings, presentation and discussion of proposals, pre-meeting preparations, etc.). Between 2013 and 2019 global mobile data traffic is expected to increase rapidly, reaching 15.9 Exabyte (15.9 billion gigabytes!) per month by 2019 [Cisco]. Also, according to [Cisco], the mobile industry would need to invest approximately $4 trillion in R&D and capex by 2020 to front such traffic expectation. All these R&D activities and such an incredible wealth of innovation should be reflected in public standard activities and hence turned into collective benefit.

In March 2015 the European Commission stated [EC]:

“The benefits of standards for European industry are extensive. Standards help manufacturers reduce costs, anticipate technical requirements, and increase productive and innovative efficiency. The European Commission recognises the positive effects of standards in areas such as trade, the creation of Single Market for products and services, and innovation.”

and

“Standardisation and Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) encourage innovation and facilitate the dissemination of technology. The Commission supports the view that standards should be open for access and implementation by everyone. IPRs relevant to the standard should be taken into consideration in the standardisation process. This would help ensure a balance between the interests of the users of standards and the rights of owners of intellectual property.”

5G, which promises ubiquitous broadband access, and the Internet of Things (IoT) are expected to bring even more benefits to society and the world economy. Innovation critical for society, like 5G, should always be facilitated by a standardization effort, as standards allow different platforms, services and devices to interoperate, enable core and strategic services for the public and governments alike, avoid lock-ins into competing, proprietary solutions, and ensure a shorter time to market for new technologies.

To tie the hands of standard setting organizations (SSOs) with baroque licensing regulation or restrictive IPR policy will result in a lack of ROI clarity that might force many stakeholders (from SMEs and universities to large R&D corporations) that are currently investing significant resources out of the standard-based framework, to the detriment of innovation. 5G can be the phenomenal innovative force that society is expecting with great anticipation if, and only if, the broadest participation is encouraged.

It is almost impossible to imagine what the future will bring us, but services and applications that were unthinkable simply a few years ago will quickly become a reality: personalized medicine, intelligent transportation, drone delivery systems, intelligent cropping, crowdsourced microcredit, just to cite a few.

The current innovation framework based on open standards has guaranteed adequate rewards to innovators, making such rewards accessible through licensing on FRAND terms. Such framework has enabled all stakeholders to take an active role in the innovation and standardization process.

“The patent system is a gift and an incentive to invest in an unforeseeable future. 5G will not simply be another capacity-increased enabler. It will change people’s lives. Investments are made thanks to the safety offered by the patent system: if incentives to invest remain, the future will be amazing [Herm].”

2.3. How to Create an “Innovation Loop”

Intellectual property is proven to be fundamental for corporate growth and competitiveness. Different business models have originated in the last decades by the growing importance of intellectual property rights.

While in the past IP was mainly considered a legal tool in order to create a competitive barrier of entry in the market, today it’s more and more representing an important asset for corporate financing.

As R&D activities are becoming more and more expensive, very few companies can finance new innovation exclusively through sales. It has indeed become extremely important to exploit IP rights to generate additional revenue streams that can fund new business development and innovation.

Through licensing, revenues from royalties for the use of a trademark or patented technology can be re-invested in the company. This creates a self-sustaining cycle in which the results of previous innovation can fund new research, generating an innovation loop, in which intangible assets acquire a tangible economic value.

We fear that this virtuous cycle could be broken. If universities and research centers, and any industry player that invests in R&D, don’t have the means and legal protection to effectively monetize innovation and forego a steady flow of capital to support development and growth, competition will suffer and, ultimately, the thriving high-tech industry that many of us have helped create will suffer.

2.4. Is Litigation Really on the Rise?

We would like to demystify a popular myth: litigation has recently increased substantially, especially in the mobile industry. An article [Katzn] by Ron Katznelson that went almost unnoticed shows that, with the exception of AIA-caused litigation anomaly of 2011-2013,3 when litigation rates in the U.S. are normalized by other economics factors like GDP, such rates have remained fairly stable for more than a century, and in fact, relative increases can be associated with significant technology improvements.

Furthermore, an academic article by James Bessen and Michael Meurer [Bess] in particular has been widely cited and used to support the argument against trolls (as broadly defined as possible to include virtually all NPEs), often cited [Chamb] to urge for institutional patent reform or policies. However, many of the assumptions of said paper have been questioned and ultimately disproved by David Schwartz and Jay Kesan in [Schwa].

A very informative, precise and well written piece of economic work overall, Schwartz and Kesan’s paper identify four fundamental weaknesses of Bessen and Meurer’s arguments. More specifically:

“(1) Figures Based on Biased Sample. Bessen & Meurer’s $29 billion calculation of the direct cost of NPE patent assertions should be viewed as the highest possible limit. The true number is very likely to be substantially lower. It is the outer bound because the survey is not a random sample; instead it likely is a biased sample, which renders Bessen & Meurer’s extrapolation of the total costs similarly biased too high.

(2) Lack of Basis for Comparison of Figures. The vast majority of the $29 billion figure consists of settlement, licensing, and judgment amounts. For economists, these are not “costs,” as they are classified in the Bessen & Meurer study, but rather “transfers.” Such transfers to patent holders are the contemplated rewards of the patent system. Furthermore, before declaring litigation costs (i.e., lawyers’ fees) too high, there must be some basis for comparison. Bessen & Meurer provide no such comparison. For further academic studies, we propose comparing them to either the ratio of lawyers’ fees to settlements in practicing entity patent litigation or complex commercial litigation more broadly.

(3) Questionable Definition of NPE. Bessen & Meurer’s calculations rest upon a questionable and very broad definition of NPE. We suggest that they disaggregate among different categories of NPE, which should be possible with RPX’s database.

(4) Lack of Credible Information on Benefits of NPEs. Bessen & Meurer’s estimate of the benefits of NPE litigation is based upon an analysis of very limited information, namely SEC filings from 12 publicly traded NPEs. We recommend a survey of NPE plaintiffs analogous to the survey of NPE defendants to provide more complete information on this issue.”

A draft paper in preparation by Katznelson [Katzn3] also helps identifying and exposing what has been referred to as “junk science” presented in the work by Bessen and Meurer. We urge all supporters of the U.S.-based Innovation Act, the TROL act, or any other legislation or policy that moves from flawed assumptions, to carefully consider those assumptions and ponder on the impact that defective economic analysis can have on a global scale.

2.5. The Growing Concern with “Patent Ogres”

In an article on IAM [IAM], a prolific inventor describes a well-known challenge that most individuals or small companies owning technologies and patents have come to face: the issue of what he refers to as “Patent Ogres.”

“A patent ogre is a large company that has a significant market position in a product or service category and protects its economic interest by suppressing, bullying and/or simply grinding into the ground smaller, more innovative competitors that have patented technologies. Faced with a small innovator with patents that potentially read on its products or services, the patent ogre […] may refuse to license the technology at market rates, […] create publicity campaigns to label the inventors as trolls, and drag them through endless legal maneuvers until they run out of money […]. Then the patent ogre continues to derive economic benefit from the technology that someone else invented or perfected.”

Without a strong patent system that can rely on injunctive relief and fair court treatment with respect to awards and fees,4 smaller entities will be left without recourse against larger corporations, with greater resources to engage in drawn out disputes. SEP owners, like any other patent owners, should have the ability to seek injunctions and monetary damages when faced with unwilling licensees.

The recent decision of the ECJ in Huawei Technology Co. Ltd v. ZTE Corp., ZTE Deutschland GmbH (Case C-170/13) [ECJ] confirms the importance of maintaining all remedies against unwilling licensees in the context of licensing standards essential patents (SEPs). In particular, the ECJ ruled that injunctive relief may be available if an alleged infringer fails to respond diligently and in good faith to a detailed written offer from an SEP holder. Moreover, if the alleged infringer rejects the SEP’s holder’s offer, then it also must promptly submit a specific written counter offer and, if no license results, the implementer must provide commercially appropriate security and maintain accounts.

We acknowledge [IAM2] that the ECJ’s decision in Huawei v. ZTE makes it clear that the foregoing obligations on implementers only arise if the SEP holder satisfies its initial burden of specifying the manner of infringement and providing a detailed written offer for a license on Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) terms. However, by making the availability of injunctive relief depend on the actions of both the patent holder and the implementer, the court highlights the critical role of the injunctive remedy to drive the parties towards a license agreement.

The ECJ confirmed that FRAND is a “two way street”: licensors accept to license on FRAND terms—and that allows SSOs to include technologies developed by the broadest possible base of stakeholders—but implementers do accept to take a license on those FRAND terms. The burden cannot be only on patent owners, especially because implementers are not forced to implement a standard. They do so if they see value in said standardized technologies, and that value needs to also account for fair rewards to the innovation ecosystem that developed the standard. “One way streets” result in free riders.

As part of the decision, the awareness of so-called unwilling licensees clearly emerges. In other words, the ECJ recognizes the existence of implementers who are exploiting all benefits of implementing somebody else’s technologies but none of the burdens that are associated with such use. It is worth noting that, although no empirical evidence of hold-ups exists, and such evidence is only anecdotal at best, there is plenty of evidence of hold-outs [Qualc]. Unfortunately, there has been more than one attempt, even by representatives of reputable institutions like the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), to suggest (support?) policy changes or even new regulation based on flawed economic analysis.

Recent policy and regulation proposals, set forth by a few players, would on the other hand protect free-riding behaviors under the noble goal to eradicate abusive litigation. Using such an excuse, countless attacks to the innovation ecosystem have been launched, including:

- The opposition to secondary markets, with the suggestion that limitations on SEPs divestments should be enforced;

- The promotion of the smallest saleable unit theory;

- The support for per-SEP value determination based on the overall number of patents declared essential to a specific standard;

- Restrictions to the attachment point for the license;

- The suggestion that injunctions are not appropriate tools for SEPs (de facto discriminating between SEPs and non-SEPs).

Such proposals would have harmed the entire standard-based innovation ecosystem to favor the bottom line of a few, turning a swinging pendulum in a wrecking ball. In fact, by limiting or eliminating the use of injunctions with the excuse of solving a hypothetical and, systemic risk of hold-ups, we might create another systemic risk based on hold-outs! Therefore, we welcome the ECJ decision, as it restores the appropriate balance and clarifies the requirements for both patent owners and implementers.

The ECJ decision provides clear guidance on the remedies available against “Standards Free Riders.” The decision, in particular, restores a needed balance in the recent discussion about remedies available to innovators, especially in the context of SEPs. Enforcement and injunctions are a matter of justice, and excessive limitations to licensing will put the entire innovation ecosystem at risk. Furthermore, suggesting specific limitations on SEPs licensing will create an illegitimate imbalance between SEPs and non-SEPs, ultimately impacting the open standard framework.

On related news [Sisv], on November 3 the Düsseldorf Regional Court issued a first instance judgment in a case that saw Sisvel as a plaintiff against a Chinese manufacturer Haier that did not take a license under FRAND conditions. The Düsseldorf Court granted Sisvel injunctive relief, based on the fact that the potential licensee refused to take such FRAND license after almost three years of licensing discussions and negotiations. This decision is one of the first indications—if not the first one—on how the ECJ decision will be interpreted by national courts.

Good news for innovators and patent owners— and every entity that engages in R&D—came from the U.S. as well [WARF]. In a flagship decision (Case No. 14-cv-62), the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin ordered Apple to pay the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) $243 million dollars for violating one single patent developed by the University of Wisconsin and used in Apple’s A7, A8 and A8X processors, found in the iPhone 5s, 6 and 6 Plus, as well as several versions of the iPad. WARF had sued Intel in 2008 over the same patent, and later settled with the Santa Clara-based company for $110 million. WARF uses the income it generates from licensing to support research at the school, according to its website.

The WARF v. Apple and Sisvel v. Haier decisions bring clarity and restore a needed balance in a debate that has lately become misleading. Too often legitimate non-practicing entities like universities, research centers and licensing companies have been accused of being patent trolls simply for enforcing their patents against infringers. As mentioned above, enforcement and injunctions are a matter of justice against those implementers that rely on others’ technologies but are unwilling to pay for them.

Without such remedies and tools, and ultimately without a strong patent system, the innovation ecosystem will suffer, and society as a whole will pay the consequences of a less innovative hi-tech sector. What is truly needed is a more reasonable solution for the mentioned true troll-behavior that does not harm good faith licensing companies.

2.6. Inter Partes Review (IPR) and the Rise of “IPR Trolls”

One unintended consequence of the institution of the (carelessly drafted, according to some) inter partes review process in the U.S. through the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) has been the exponential growth of weak or even groundless post grant challenges, as there is no standing requirement for IPRs, with the exception of covered business methods. New legislation unnecessarily shifts the burden to patent owners and small entities with limited resources in particular, to the advantage of large corporations and entities with deep pockets.

As [Quinn3] explains:

“While it is a laudable goal to make it easier to challenge obviously absurd patent claims, the way that post grant procedures were created does little other than ensure that any patent owner with a commercially valuable patent will face endless challenges.”

Unfortunately, a new breed of patent trolls have emerged that leverage post grant procedures to gain otherwise unjustified profits. Kyle Bass, founder of hedge fund Hayman Capital Management, has been under fire for shorting stocks of pharmaceutical companies after filing (often phony) challenges against their patents covering chemical compounds [WSJ].

In Europe, where post grant challenges exist for a limited period of time after grant (the so-called opposition phase), it is not uncommon to have patent rights challenged by proxy, non-practicing entities that protect the identity of the real challenger. There have been cases of companies filing blanket challenges to all newly-issued patents by specific companies, suggesting a clear strategy to target the whole industry or simply somebody else’s competitors. However, such challenges shift the burden to the patent owner, who is now forced to spend time and resources to fight back, and determine long delays in the enforceability of the patent. Therefore, we find it appropriate to refer to companies employing such tactics as “IPR trolls.”

An editorial by the New York Times [NYT] commenting on the recent WARF v. Apple decision [WARF] introduced the expression “efficient infringing” to describe the behavior of some modern corporations, mainly in the Silicon Valley: “That’s the relatively new practice of using a technology that infringes on someone’s patent, while ignoring the patent holder entirely. And when the patent holder discovers the infringement and seeks recompense, the infringer responds by challenging the patent’s validity.” The value-added of the technology is often demonstrated by the broad and repeated use of said technology by the infringer.

2.7. Why Creating Global Implications to Solve Local Nuisances?

Before relying on simplistic assumptions and/or overly-broad generalizations, it is important to recognize who the bad actors really are. Statistics by Patent Freedom, as reported by [Niro], show that 56 percent of NPE patent lawsuits are brought by the original assignees— hence the inventor’s company—of the patents involved. Interestingly, and yet little popularized, that number increases to 80 percent when one includes companies that share licensing revenues with inventors or original assignees of said patents.

It is important to notice that the policies of SSOs have an effect on how SEPs can be used in virtually every jurisdiction. The obligations imposed by SSOs upon patent owners submitting their technologies to standardization have global ramifications. When we focus on the extortionist practices of so-called trolls, we see that their practices are contained within a very limited number of jurisdictions, of which the vast majority are located in the U.S. [Muell].

More importantly, when the practices of these companies are examined, we already understand that these practices do not conform to the now current FRAND obligations with which these companies’ patents are encumbered. These practices find their business model in the fact that it is often more expensive to defend oneself against a bogus claim of such a company, than to just pay the settlement fee. Due to this circumstance, these companies are not expected to act differently when the obligations of SSOs will become more restrictive. The often-cited example of a company requiring payment of obscene fees for the usage of Wi-Fi routers in hotels and the like illustrate this situation perfectly. These claims were made, in spite of the obviousness that these claims were not conforming to FRAND obligations, but based on cost of litigation vs. cost of settlement.

Ultimately, the business model of patent trolls—the extortionists, not all NPEs—relies on, and is priced upon, the high cost of U.S. litigation. To some extent, the problem of patent trolls is largely a U.S. problem only. A U.S. problem which is rooted in the legal system, rather than the patent system and the practices of SSOs. Why do we need to create global implications, and potentially harm the world economy, to solve a nuisance which primarily (if not only) exists in the U.S.?

3. Proposed Changes to SSOs’ IP Policies

The debate about patents has recently shifted to policy and, in particular, to whether SSOs should revise their IP rules for participation in the standardization activities. The rationale of some proponents of very restrictive policy is that imposing constraints to SEP owners will help curb abusive behaviors.

Recently, the IEEE has changed its IP policy [IEEE], [IEEE2], and has inflamed an already controversial debate. Although we give IEEE credit for trying to provide some guidance to the industry, their solution seems a bit too drastic, short-sighted, and, some would argue, biased.

A paper by Katznelson [Katzn2] carefully explains the effects of the updated IEEE IP policy which deviates from what the author refers to as “FRAND Harmony,” or the uniformity in non-definition5 of FRAND terms by SSOs. As the author puts it:

“IEEE’s new departure from de facto industry standard licensing practice will put parties into irreconcilable legal positions: SEP licenses for new standards may not simultaneously conform to the new FRAND terms mandated by the 2015 IEEE patent policy, and to legacy FRAND terms in the old licenses that necessarily follows legacy technology. This will undermine dynamic efficiencies in innovation where new standards incorporate other legacy standards by reference as “normative,” and where standard amendments are rolled-up into new revisions of the standard. Under this new patent policy, IEEE Societies will be handicapped in developing new standards that build on legacy standards.”

The updated IEEE patent policy is a substantive change from its precursor, with changes that require additional material binding concessions from SEP holders who agree to be bound by it. At the same time, such additional concessions do not change the irrevocable contractual obligations that SEP holders made to implementers under previous legacy LOAs not to discriminate against them, in particular, by later providing more favorable terms on the same SEPs to other licensees. As [Katzn2] explains, under the updated IEEE patent policy, those terms are necessarily more favorable to new licensees.

In the next subsections, we will be more specific about the IEEE updated policy and similar policy changes that have been proposed to other SSOs, addressing in particular some of the most controversial proposals relating to the following:

- Injunctions:

Supporters of the updated IEEE IP policy argue that injunctions are not appropriate for SEPs, and should be heavily regulated or entirely avoided. We argue that injunctions are a property right and the only remedy to maintain a balance between patent owners and implementers. - Smallest saleable unit theory:

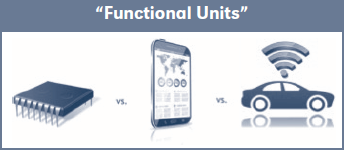

We will explain why the use of the so-called “smallest salable unit” theory fails to recognize the value of patented technologies. On the contrary, the “independent functional unit” concept will be introduced.

• Per-SEP value:

Some have argued that the value of each SEP should be calculated as the total value of the technology divided by the total number of SEPs (or patents in general) covering such technology. While this scheme has some merits, it fails to recognize the quality of the patent under consideration and the contribution of the inventor to said technology. - Attachment point:

Some large industry players have argued that licensing upstream, hence from the device manufacturer upwards to the chipset manufacturer, will help limit frivolous litigation. We argue that this proposal does nothing to curb litigation, and is only deceptively instrumental to justifying the smallest saleable unit theory. - Sale of SEPs:

Rules regulating the sale of SEPs already exist in most SSOs’ IP policies. Some industry players seem to suggest that the sale of SEPs always has a second end, and buyers are almost always patent trolls. However, they ignore (or are shamefully silent to) the reasons why patents are transacted and the associated need for secondary markets. - Arbitration as binding procedure:

Instead of supporting innovators against free-riders, imposing rules on how enforcement should be managed shifts the burden entirely onto patent owners. Arbitration and mediation are two legitimate tools that patent owners can already use. Nevertheless, requiring arbitration as a prerequisite for injunctions renders enforcement virtually impossible.

Although the focus of the IEEE updated IP policy, as well as the debate around SSOs’ IP policies, is technically on SEPs, some proposals—like the smallest saleable unit theory—have implications that go well beyond SEPs.

Proponents of drastic changes in SSOs’ IP policy should carefully ponder on the implications such changes will have for the ecosystem and for society as a whole. Policies based on Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) terms have guaranteed the broadest participation to standardization efforts. By proposing boundaries or limits to FRAND within IP policies, we would be combining case law with policy, or, even worse, making up creative, hypothetical case law into patent policy. This would create a confusing tangle of separate concepts.

As a matter of fact, the underlying assumption of proponents of updated IP policies is that current SSOs’ policies are not working. This is simply not true, and unsubstantiated by facts. In the previous sections, we have tried to demystify and challenge incorrect assumptions. In the following subsections, we would like to address and challenge some specific proposals that have been suggested as possible “solutions” to a problem that is, in reality, more like a nuisance perpetrated by few bad actors and, to a large extent, the by-product of the U.S. legal system. As the adagio goes: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

3.1. Injunctions, Injunctive Relief and SEPs

As previously mentioned, injunctions are a property right and a necessary tool to maintain a balance between patent owners and unwilling licensees (see the previous discussion about “patent ogres”). Even in the presence of SEPs, there are no other remedies left to patent owners when negotiations completely fail or are purposely stalled by potential licensees that refuse to take a license. The ECJ has recently effectively clarified this matter [ECJ], with what we perceive as a balanced approach that takes into consideration the industry’s different needs and motivations. On the other hand, proposals that want to limit the use or completely prohibit injunctions shift the balance to the big companies even more to the detriment of small companies. These arguments frame the debate in a way that is skewed towards a negative view of any effort to enforce patents through the judicial process by suggesting that patent holders are trying to coerce licensees with unjustified licensing demands, irrespective of what those demands are.

One of the main concerns of unbalanced policies and regulations when dealing with SEPs is the consequences that such policies will have on the standard setting organizations themselves, participation to such standardization activity and, after all, the commercial success and technological relevance of said standards. Many companies and innovators will weigh participation to standardization activities also in light of the potential Return on Investment (ROI) that they could generate by allowing open access to their technology, and some, to the detriment of innovation, may decide to avoid participation at all, or revert to proprietary, closed solutions or trade secrets instead. In essence, innovators will face significant risks by investing in R&D without a solid ROI outlook; yet, without valid technical contributions by all industry players, entire standard activities may be jeopardized.

Some have suggested to tie injunctions to the refusal by potential licensees to participate in an arbitration or mediation procedure. In our view, however, any judicial process, including arbitration or mediation, should be treated as an additional tool to solve a licensing negotiation, not as a binding procedure. Without any risk of injunction or monetary damage, some unwilling licensees may still have the ability (and certainly the interest) to stall the negotiation indefinitely. Without any remedy, smaller companies, universities and individual inventors will have no chance against larger companies.

Rather than policy, the discussion about patent licensing and enforcement is primarily a legal argument that goes well beyond SSOs patent policy, and whose implications can have significant social impact.

3.2. Smallest Saleable Unit Theory

We trust everyone in the industry would agree that the innovators of the mobile wireless industries should be remunerated for the benefits they bring to the world economy; the problem is to determine the right amount. Is it fair to restrict this amount on a percentage of the smallest saleable unit? Clearly the value is not provided only by the chipset, but by the entire phone connected to, and operative on, the mobile network.

One authoritative opinion about RAND royalty comes from the Court in the Ericsson v. D-Link case [Erics] which rejected the argument that a RAND royalty must always be based on the “smallest saleable unit” and explaining that “where the entire value of a machine as a marketable article is ‘properly and legally attributable to the patented feature,’ the damages should be calculated by reference to that value.”

Even if most of the wireless standard essential features are implemented in a single processor/chipset, is it fair to say that FRAND royalties should be based on the smallest saleable unit (i.e. the modem chipset)? Is the modem chipset really the smallest saleable unit as identified by users, manufactures and the market as a whole?

To answer the questions posed and support our position, we first need to understand what the real marker of a smartphone implementing standard essential features such as, for example, Long-Term Evolution (LTE) [LTE] or Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11) [WiFi] really is.

When users buy a mobile phone, they benefit from a wealth of standard-essential features. However, most of them (us), do not really look to buy a chipset implementing those features, but rather they choose a smartphone for its complementary characteristics. In fact, consumers consider features such as touch screen size, video and camera quality, processor speed, the amount of memory, data transfer speeds, etc. They may be interested in specific wireless technologies (2G/3G/4G, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, NFC), a GPS receiver, and sometimes support for precise video and audio codecs. However, users do not even ask themselves if the phones are compatible with the existing mobile networks. Because they certainly are! Nevertheless, many of the features sought are available only thanks to the capabilities enabled by wireless standards.

In the past, a mobile phone was a device mainly dedicated to communicate with its own network, allowing a user to make voice calls and send text messages, the so-called Short Message Services (SMS). The processor at that time was dedicated to such features. Today a smartphone may have different hardware components; sometimes these components exist as different chips in a device. Today, the trend in mobile technology is to save battery life, so new power-efficient systems (so-called System on a Chip, or SoC) do include all the capabilities required by the phone. In fact, bringing them into a single device provides faster communication and reduced power consumption.

A smartphone such as an LTE smartphone is composed of hardware elements with means for communicating among them. Better-known components include: some memory, display/touchscreen, processor, camera, wireless modem, battery, sensors, etc.

In today’s trend, the main smartphone processor integrates several modem capabilities (for example, the Qualcomm Snapdragon 8XX series integrate LTE modem capabilities, as well as Bluetooth capabilities), this means that the processor itself is capable of managing the transmission through the radio interface with base stations or access points. As a consequence, many standardized features are, to be precise, implemented by software in the processor. Such features include, among others: transmitting packets to a base station, coding and decoding video streams, receiving from a remote server an IP address. As a colleague once put it:

“Give an engineer a Wi-Fi chipset and an antenna: what would he do with it?”

Modern smartphones have processors similar to those installed in personal computers, but optimized to operate in low power environments. Like a PC processor, a mobile processor is responsible to run an operating system and to manage all the peripherals.

A computer processor is shipped without any software components, thus the cost of a computer processor depends on designing and manufacturing the hardware materials of the processor. There is no huge investment excluding those strictly related to designing the processor itself. Computer processor manufactures such as Intel or AMD do not need to implement standardized features. Once a computer is assembled with all the physical essential devices (motherboard, processor, video graphics card, etc.), the computer will need a third party operating system (OS) to work. A computer processor costs on average 300$, an operating system such as Windows 8.1 around 100$. The price of these components are set in order to re-pay the cost to design, build, market and sell them.

In the mobile world, a smartphone is equivalent to a computer, the mobile processor is similar to a computer processor, and the software of a smartphone has many parts, such as the operating system, the communication software, software for localization, software for sensors, etc.

Many patent battles for software-based features are in place today: Oracle v. Google, Microsoft v. Google, and many others. Plaintiffs in these cases do not demand royalties based on the “smallest saleable unit,” and in fact their royalty expectations are generally much higher, only because their software features are not part of a public standard. On the other hand, communication features—which are actually implemented via software—are the result of years of massive investments in R&D by all participants to standardization activities. It is not unreasonable to expect that many of such participants will reconsider their investment strategies or abandon support to public standards if RAND royalties ought to be unfairly based on the “smallest saleable unit” principle.

A more appropriate attachment point should make use of the “functional unit” concept, which is the finite, independent and fully-functional assembled product. We support royalty rates calculated per functional unit, hence recognizing the value added by the licensed technology and the investments behind the development of said technology. Such functional unit cannot be the chipset, as it is unable to function independently in the hands of a user, although sophisticated and skilled. At the same time, the functional unit needs to recognize the real value added by the patented technology, but not more. As an example, many cars today include wireless technologies such as LTE and Wi-Fi. Clearly, the functional unit cannot be the car itself, but rather the end-user ready device enabling this connectivity. Therefore, royalty rates should be calculated starting from the smallest functional unit that include such ready-to-use technologies, hence devices such as mobile phones, tablets, etc.

A more appropriate attachment point should make use of the “functional unit” concept, which is the finite, independent and fully-functional assembled product. We support royalty rates calculated per functional unit, hence recognizing the value added by the licensed technology and the investments behind the development of said technology. Such functional unit cannot be the chipset, as it is unable to function independently in the hands of a user, although sophisticated and skilled. At the same time, the functional unit needs to recognize the real value added by the patented technology, but not more. As an example, many cars today include wireless technologies such as LTE and Wi-Fi. Clearly, the functional unit cannot be the car itself, but rather the end-user ready device enabling this connectivity. Therefore, royalty rates should be calculated starting from the smallest functional unit that include such ready-to-use technologies, hence devices such as mobile phones, tablets, etc.

We welcome the work done by the Next Generation Mobile Networks (NGMN) consortium in their white paper on 5G [NGMN]: moving from specific use cases, they have identified critical requirements and challenges that 5G networks need to address and solve. NGMN’s top-down approach reinforces the need to look at the functionalities that the new technology will bring to consumers through compliant products when connected to the network, and not merely at the silicon or module allowing such connectivity. A connected thermostat’s value to the customer is not merely the value of a thermostat and a Wi-Fi module, but rather the added functionalities that the manufacturer can offer and the consumer enjoy.7

In summary, the invention is generally not the product itself, but rather the functionality and the enablement. One should focus on the use of the technology and what such technology enables, rather than which element of the product incorporates the claimed technology. What is the intended use for the technology? What functionalities in the product are enabled by the claimed technology? And what patents cover the intended use and the enabled functionalities therein? If the correct level of the implementation of a patent claim were the chipset and not the functional unit or system, negotiations between patent owners and implementers would be forced into a patent-by-patent debate as opposed to a portfolio view. The former scenario would be immensely burdensome to both patent owners and implementers without giving implementers any added element to evaluate the contribution of patent owner’s technologies to their products.

In addition to the above discussion, courts have refused the smallest saleable unit theory in several occasions, most recently in CSIRO v. Cisco8 [CSIRO]. First, we recommend not confusing case law with policy. Second, we reject the notion that concepts that have been refused by Courts and tribunals worldwide should be considered within IP policies.

For the above reasons, we cannot support the “smallest saleable unit” theory and we urge the industry, regulators, SSOs and all stakeholders to recognize the fallacy of such argument. In any case, we acknowledge that the issue of appropriate SEP royalty methodologies is currently being addressed in the courts in various jurisdictions, and therefore it is highly misleading to state that a royalty “must be” calculated in a certain way.

3.3. Per-SEP Value and Royalty Demands

While some proportionality rules or an analytical framework to calculate royalties often helps licensing negotiations, pure proportionality entirely fails to account for quality and strength of the licensed technology. Some technologies and contributions are fundamental, revolutionary and unavoidable to achieve better performance or fundamentally new systems. Failing to recognize this essential driver of technological progress would be a far cry from fairness, and could represent a disincentive for innovators to invest time and resources in research.

Ultimately, we strongly favor a negotiation approach that will let market dynamics achieve an acceptable compromise and balance the interests of both patent owner and implementer.

3.4. Attachment Point and Licensing Upstream

Some have suggested that licenses should be granted upstream from manufacturers and distributors, and at the chip manufacturer level. The argument is that assertions against customers and end users will be reduced or eliminated because patent owners cannot seek royalties at multiple levels of the supply chain for the same patent.

We support the principle by which royalties can only be charged once throughout the supply chain. However, the attachment point cannot be decided by SSOs policies, as it is explicit in patent law that any use, sale, manufacturing of items practicing the patent claims is an act of infringement, and such use, sale or manufacturing require a license.

The weakness in the whole “upstream” argument is that such proposal will not prevent any frivolous lawsuits. Even with a royalty-free licensing rule imposed by an SSO, a patent troll could potentially try to ‘scare’ SMEs into payment of nuisance fees, by claiming patent infringement and an obligation to pay based on a loophole or exception to the rule, even though the claimed obligation might be tenuous or simply unenforceable, just because defending oneself in court in the U.S. is likely to be more expensive than paying the settlement fee. Said proposal does not address this issue in any way. On the other hand, it shifts the balance to big companies even more to the detriment of small companies and individual inventors. These smaller entities will have even more difficulty to get a fair compensation for their technologies, which implementers could incorporate effectively free of charge.

As previously mentioned, said “upstream” proposal will have global implications in order to fix a nuisance which primarily exists in the U.S. This is in any case due to the U.S. legal system, rather than the patent system or SSOs’ policies, and revised policies will not change this abusive behavior.

3.5. Sales of SEPs or Any IP Asset

Generally, rules regulating the sale of SEPs already exist in most SSOs’ IP policies, and FRAND or other commitments made by the original patent owner during the standardization activities usually stay with the patents even if ownership is transferred.

Recent challenges to IP policies seem to imply that the sale of SEPs has always a second end, and buyers are almost always patent trolls. That is simply not true ,and unsubstantiated by evidence. Industry players suggesting that sales of SEPs should be overly regulated or discouraged ignore or simply deny the reasons why patents are transacted, and the associated need for secondary markets.

Companies selling SEPs range from operating companies looking for diversification to small entities and individual inventors who stand no chance against tech giants and need financial partners. Sellers can be in distress and need to respond to investors or shareholders. Universities and research centers can decide to divest favoring short term returns to longer term licensing negotiations. Buyers, on the other hand, normally have a business reason—either financial or industrial—and are looking for profiting from the acquisition, similarly to any other asset transaction.

Restricting the ability to transact SEPs in a fluid market will have only two consequences: (i) depress revenues for innovators, and (ii) guarantee implementers access to patented technologies at an unjustifiably low price with no market base.

3.6. Arbitration as a Binding Procedure Before Injunctions

Instead of supporting innovators against free-riders, imposing rules on how enforcement should be managed shifts the burden entirely onto patent owners. Arbitration and mediation are two legitimate tools that patent owners can already use, at their discretion, against infringers. These tools have been used successfully in certain circumstances, and have been proposed in the past to resolve lengthy, controversial negotiations. In a few circumstances, arbitration has been mandated by courts [Sobi].

However, by requiring arbitration to be agreed upon by an infringer on a patent-by-patent basis, enforcement of an entire portfolio, especially a large one, becomes virtually impossible. Furthermore, we see no reason to replicate case law into patent policy. The two matters serve different economic purposes. As mentioned previously [Katzn2], incomplete contracts often enhance economic efficiency.

The IEEE is de facto banning injunctions for patent owners agreeing to the new IP policy. This is not only in violation of a fundamental property right but, as we explained earlier, puts the IEEE at odds with other SSOs and even its own legacy standards by deviating from “FRAND Harmony” [Katzn3]. Ironically, a patent owner may find itself in the absurd situation of negotiating a portfolio license with potential licensees where a subset of the portfolio could be used for injunctions against free-riders, and another subset shall be arbitrated with the same free-riders.

4. Alternative Scenarios

Rather than imposing all sort of restrictions to participants in the standardization process, we advocate a balanced, transparent framework that will need to serve, and take into account the requirements of, all stakeholders and the whole industry.

SSOs could be instrumental in promoting an efficient licensing framework. In our opinion, such framework could provide the following:

- Transparency in the licensing offer:

Transparency is key in order to deliver confidence to the marketplace, especially during the standardization process. - Confidence about the value proposition, provided throughout the standardization process:

The value proposition is also crucial; any licensing offer needs to offer value and efficiencies to potential licensees. - Certainty in the economics, to be defined early in the process, to both licensees and licensors:

By defining the economics early in the process, and taking into consideration all interests and market variables like use cases and products, the industry could deliver certainty to the marketplace. Hence, costs could be allocated by all implementers and incumbent market players early in the process.

In an effort to guarantee fairness to all stakeholders and restore a balanced approach to licensing, the ecosystem should focusing on solving the issue of so-called “unwilling licensees” at the source; by providing certainty and predictability, all market players will have ample opportunities to recognize the value proposition of the licensing offer.

One further tool to enhance efficiency is aggregation through patent pools or joint licensing programs. Said pools or licensing programs could be established early in the process, and discussions about licensing frameworks could already be entertained during the standardization process. In this respect, the DVB Consortium has always been very active and supportive of early licensing discussions, with the twofold objective of ensuring technology adoption and balancing the needs of both innovators and implementers.

Several authors have investigated the efficiencies and advantages of patent pools, or other patent aggregation models like joint licensing programs, citing both economic theories and empirical evidence. Aggregation models offer a “one stop shop” that reduces transaction costs and lowers barriers of entry, hence increasing competition. The benefits of standardized technologies and the economic interdependence with patent pools have been a widely-studied academic topic [Pohl], [Pohl2]. Some authors (see, for example, [Uijl] for a discussion about licensing in the optical disk industry) have even suggested and encouraged the use of “pools of pools” in order to further enhance efficiency and offer a license to all non-competitive, standardized technologies that are implemented in a product.

Lastly, we would like to comment on cost of litigation and the so-called “fee shifting” concept9 that has recently been at the center of the debate in the U.S. Here, too, we support a balanced approach that will not place too much burden on patent owners or make it impossible for industry players such as universities and individuals to seek remedies through the court system. An example which could be perceived more reasonable is awarding the cost of litigation in the event of abuse of the legal system. The U.S. Supreme Court already made this available for blatantly abusive patent claims [Oct].

Instead of curbing litigation, the current environment that some companies, especially in the U.S., are promoting is achieving the opposite goal. This is no surprise; eliminating or reducing the risk of getting sued for patent infringement or facing injunctions has inevitably led to an increase in free-riding behaviors. In an absurd article that recently appeared in The Wall Street Journal [Chien2], Prof. Colleen Chien went as far as to provide a cheat sheet for free-riders to deal with licensing demands:

“The best way to deal with a patent demand may be to […] do nothing”

Unless of course the demand comes from a large competitor or a well-funded patent owner, and in general those entities that are willing to use the court system to achieve their goals. The results of this strategy, coupled withefficient infringing behaviors described earlier [NYT], are evident to any unbiased observer: First, smaller companies and sole inventors stand no chance against ogres without the help of intermediaries.10 Second, patent owners are forced to become even more aggressive and litigious. Interesting.